bfinance insight from:

Thibault Sandret

Director, Private Markets

Since the pandemic began, developments in the shipping sector have reverberated across the global economic landscape. Looking ahead, regulatory requirements around carbon emissions will drive transformative change. Investors are cautious—but they are also sensing opportunity; maritime leasing is answering asset owners’ appetite for alternative finance strategies that provide diversification, income and even environmental impact.

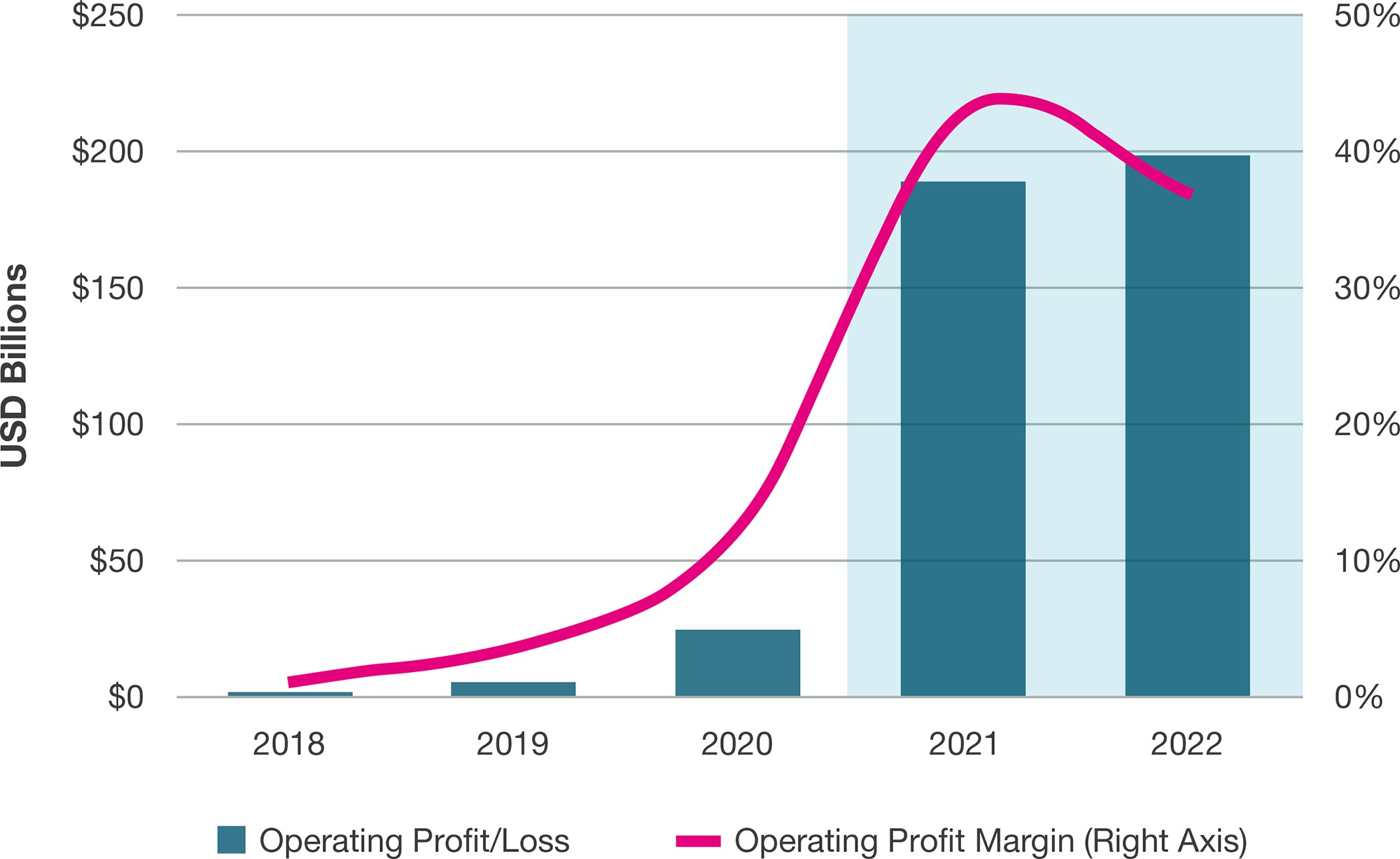

Although port congestion sparked by the pandemic has played havoc with supply chains—and contributed to surging inflation in developed markets—it’s been a boon for the shipping industry. Almost overnight, maritime operators running container ships have been able to raise freight rates to historic highs. According to Drewry Maritime Financial Research, the container shipping sector is expected to post record operating profits of USD190 billion for 2021, achieving an unprecedented profit margin of 43%, and the firm expects to see the industry’s operating profits edge even higher this year, to nearly USD200 billion. (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: CONTAINER SHIPPING INDUSTRY OPERATING PROFIT FORECAST FOR 2022

Source: Drewry Container Forecaster

Against this backdrop, investors are sensing opportunity in the sector—even though it is essential to proceed with caution. For a start, not all maritime shipping sectors are likely to see similarly high operating profits in the months ahead: dry bulk ocean carriers and tankers are subject to very different supply-and-demand dynamics than container ships. Furthermore, few investors have forgotten just how narrow operating profit margins actually were in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC), when an estimated 12% of the world’s global fleet of ocean freight carriers stood at anchor, empty and unmoving, as operators struggled to make money in a fiercely competitive environment.

The current cycle, however, looks somewhat different. Although the pandemic triggered a major contraction in global trade, the catalyst was external to financial markets—and the subsequent recovery that began in late 2020 has been remarkably swift. Pre-existing consumer trends, such as the rapid expansion of global e-commerce, have accelerated at a faster pace than they might have done in a world without COVID-19. And the global shipping industry itself is evolving: Maritime transport companies are now working to meet strict new regulatory environmental standards by replacing or retrofitting ships and switching to cleaner fuels.

In response, ship operators are actively hunting for new sources of investment capital to upgrade their fleets. At bfinance, we have recently assisted a number of sophisticated investors with targeted searches for managers specialising in maritime leasing strategies. Although the maritime sector is notoriously volatile and cyclical, leasing strategies exhibit markedly less risk than pure equity plays in the sector and offer relatively healthy and stable income-oriented returns. Investors also get exposure to potential capital appreciation—or slower depreciation—of the underlying assets, which can confer an additional layer of protection in an inflationary environment.

An industry facing transformative change

The crux of the opportunity in maritime leasing centers on the continued, almost inexorable growth of the shipping industry, which accounts for 80%–90% of total global trade by volume. Flashy it is not, but shipping is by far the most cost-efficient way to transport goods and raw materials over long distances. It is also the most fuel-efficient form of transportation, accounting for less than 3% of global carbon emissions annually.

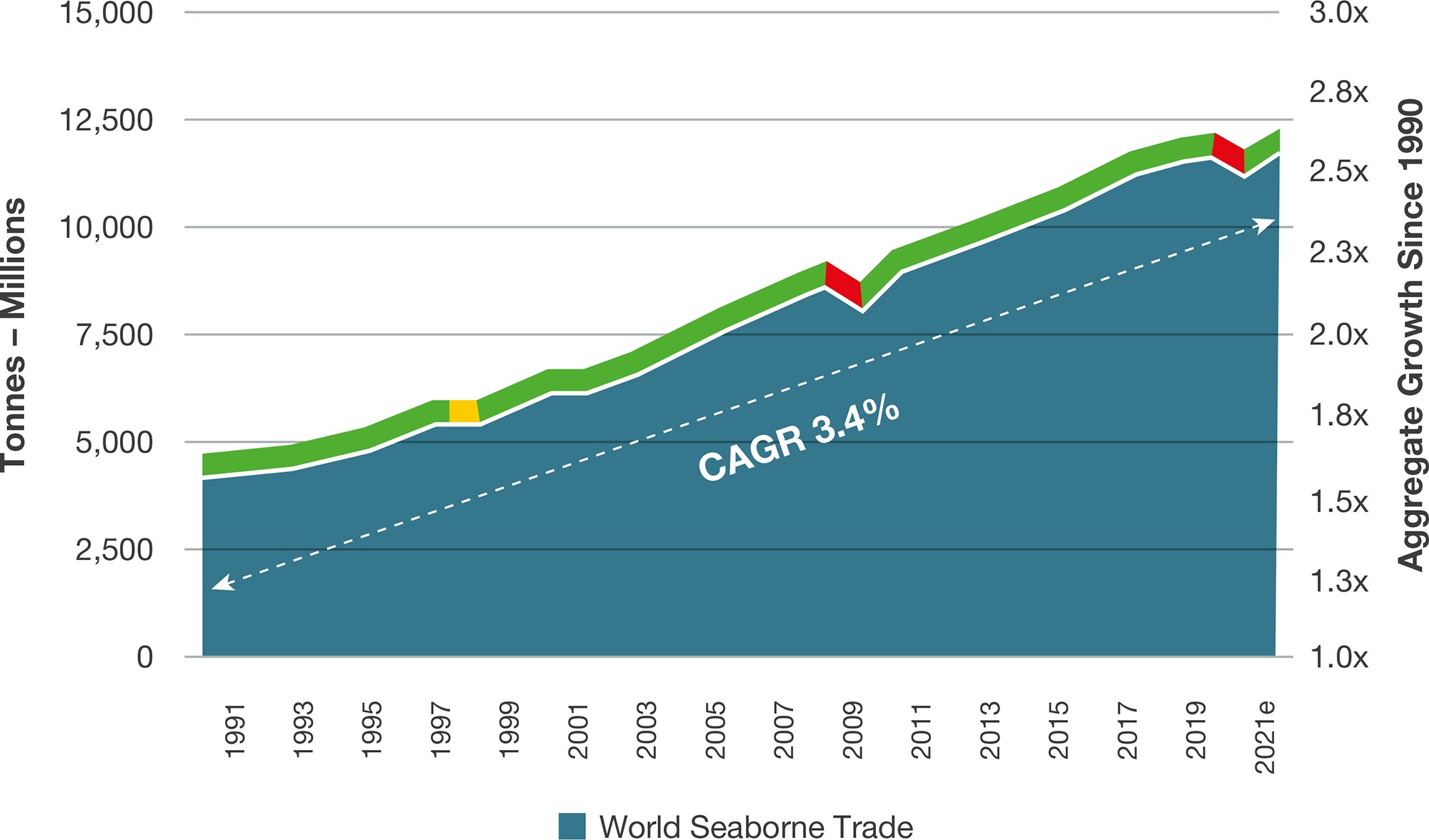

Demand is driven by long-term secular trends, such as economic growth and global trade expansion, as well as the growing demand for commodities, agricultural products and energy sources. Since the 1990s, the industry has benefitted from gradual—but remarkably consistent—upward momentum as seaborne trade volumes have increased. Notwithstanding major disruptions in 1997-’98 (the Asian financial crisis), 2008-’09 (the GFC) and 2020 (the onset of COVID-19), the industry has delivered a compound annual growth rate of 3.4% (Figure 2).

“The fact of the matter is that maritime assets are critical infrastructure in the global economy,” says Henrik Ramskov, managing partner of Danish maritime investment firm Navigare Capital. “Even if globalisation slows down or comes to a standstill—and we see massive economic regionalisation—we will still need to transport goods, and shipping is the most climate-efficient way to do that.”

Although seaborne trade volumes dropped markedly at the outset of the pandemic, they recovered at an astonishing pace, surging by an estimated 7.1% year over year in 2021, according to IHS Markit, which is now forecasting growth rates of 4.1% in 2022—and a compound annual growth rate of 3.2% going forward, through 2030.

FIGURE 2: WORLD SEABORNE TRADE

Source: Clarksons Research

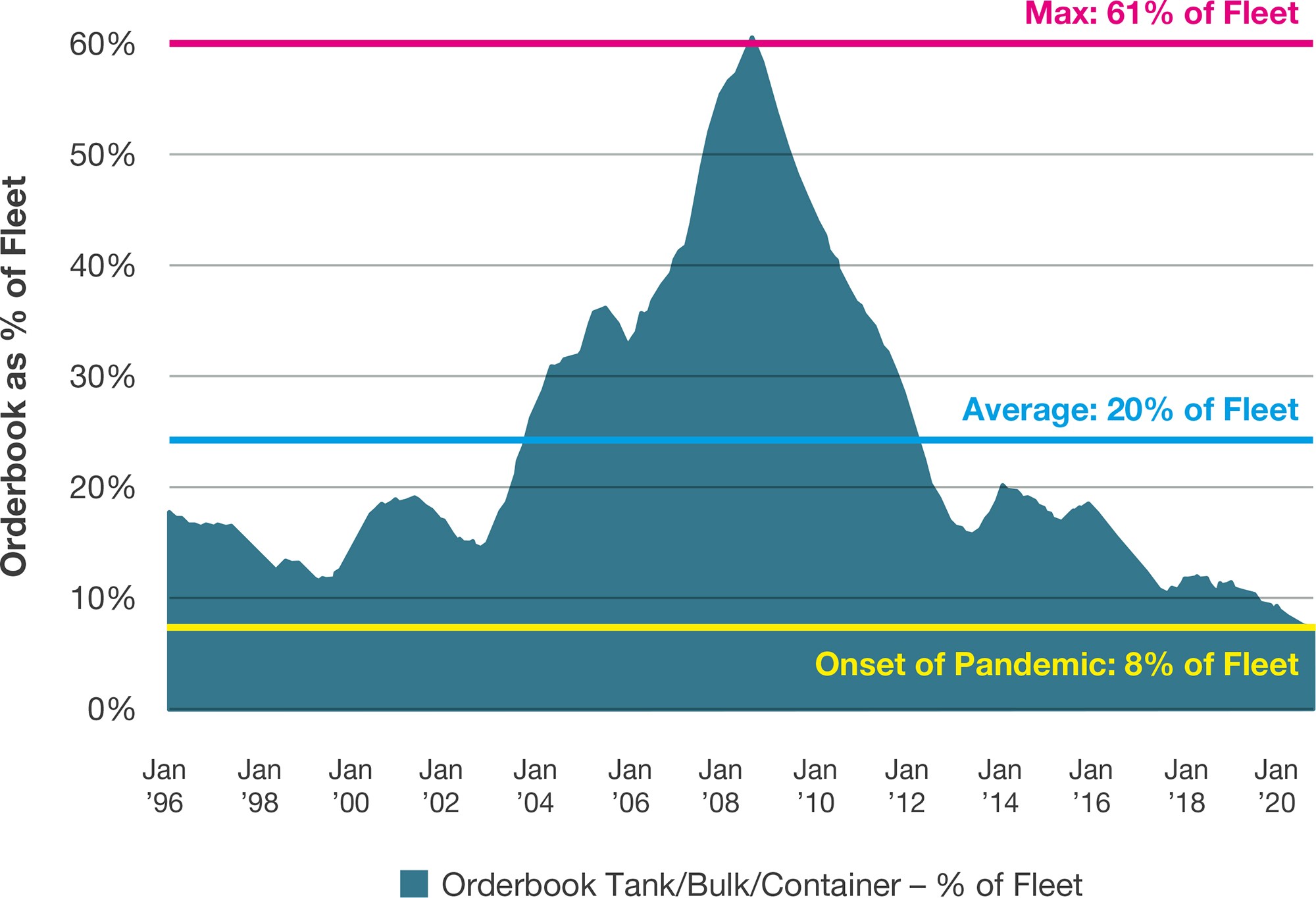

Orderbooks for new ships, however, have not kept up with rising demand. At the start of the pandemic in 2020, the orderbook-to-fleet ratio stood at just 8% compared to an historical average of 20% and a peak of 61% at the time of the GFC in 2008–’09 (Figure 3). Although new orders for transport ships have picked up slightly since the global economic recovery took hold in late 2020 and early 2021—and now represent 9%–10% of the global fleet—they remain well below the 20% historical average. The relative dearth of available ships coupled with the historically low orderbook base (and spiking demand) has put maritime operators in a commanding position to set freight rates and increase their profits.

FIGURE 3: ORDERBOOK AS PERCENTAGE OF GLOBAL FLEET

Source: Clarksons Research

Gaining access to new vessels, however, is no longer a straightforward proposition. Strong as their earnings have been over the past 12–18 months, operators face fundamental challenges that affect the financing and development of new vessels. Traditional providers of long-term capital, namely investment banks, have pulled back just as operators have begun to grapple with new environmental regulations that will require the deployment of innovative—and highly technical—solutions to replace diesel-powered engines.

These demands are coming fast. In 2018, the United Nations’ agency for shipping and marine regulation, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), implemented a new greenhouse gas (GHG) strategy designed to reduce GHG emissions from ships by at least 50% no later than 2050. The IMO has since tightened other existing regulations, most recently limiting sulfur content in ships’ fuel to 0.5% (down from 3.5%) as of 2020.

In 2021, the European Commission proposed adding maritime transport to the European Union’s carbon market for the first time, redoubling pressure on shipping operators to limit carbon emissions. By 2023, ship owners will have to buy permits under the European Union Emissions Trading System (ETS) when their ships pollute—or else face possible bans from EU ports. Beneficial as these measures will be for marine ecosystems, they inevitably mean that existing fleets may be destined for obsolescence long before their engines can be adapted to burn less-polluting, low-carbon fuels.

As a consequence, shipping operators are now searching for alternative providers of stable, long-term financing to prepare for industrial-scale transformation. The potential for investment managers to capitalise on the funding gap and take part in the shift towards environmentally benign and fuel-efficient fleets—while profiting from exceptional freight rates—is attracting significant interest from investors.

Fund managers join the fray

No one is in any doubt that the industry requires fresh sources of capital to evolve. The need is now evident: since 2010, the top 40 international banks have collectively reduced their maritime industry exposure by one-third, from USD450 billion to USD300 billion. The retrenchment has been particularly pronounced among European banks, which have slashed their exposure to maritime transport assets by 50% even as the overall global fleet size has grown by 47% over the past decade.

The demand for financing, however, is only set to continue growing. In Europe alone, the annual funding gap is now estimated to range between USD50 billion–USD60 billion. The seaborne freight industry has also suffered from a shortage of private and public equity financing for ship building—largely because investors incurred losses from speculative investments in maritime transport companies between 2013–2019.

The industry’s profile as an alternative asset class has clearly suffered as a result: In 2019, the industry posted only USD2.9 billion in equity offerings—down from USD14.5 billion in 2014—and no private equity investments were made in the sector. As a result of the reduced availability of capital, however, the balance of power is now shifting: the cost of capital is rising, and alternative capital providers are also able to negotiate more investor-friendly terms when structuring lending or leasing contracts.

Pathways to shipping exposure: the manager universe

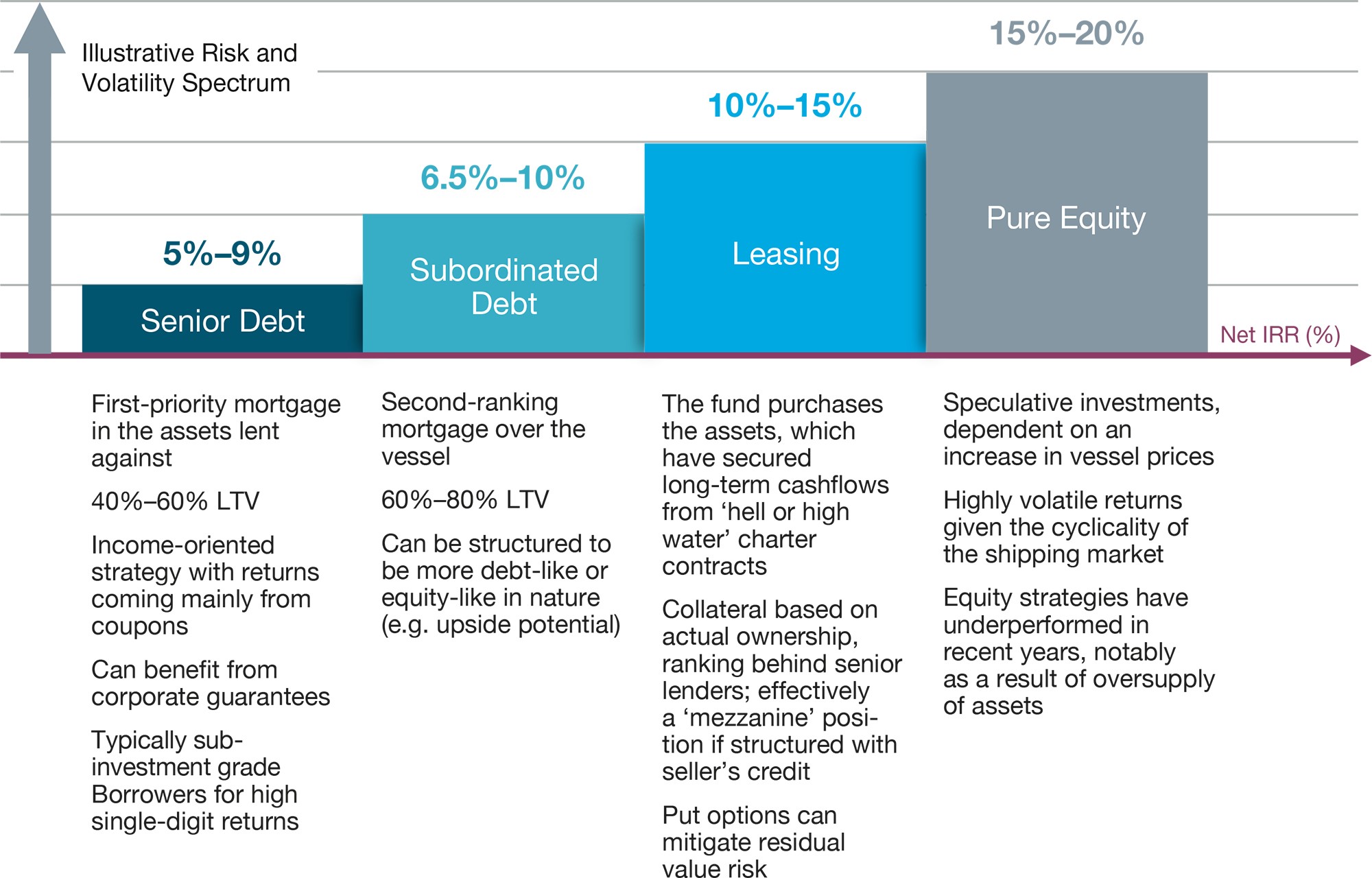

Over the past few months, some maritime stocks have soared to tantalising heights, but investors would be wise to look beyond the attractions—and volatility—of equity strategies and focus on the potential for long-term leasing strategies to deliver stable, reliable income generation above the potential capital appreciation of the underlying assets (Figure 4). Leasing strategies typically target net returns in the 10%–15% range, primarily driven by long-term contractual cash flows, and can benefit from asset collateral as well as inflation protection.

FIGURE 4: LEASING CAN OFFER ATTRACTIVE RISK-ADJUSTED RETURNS

Source: bfinance

Perhaps the single most important element that investors may want to focus on, however, is the manager’s ability to construct a well-diversified portfolio by sourcing transactions across an array of market segments. As in any alternative asset class, identifying strong managers with extensive industry networks makes a material difference to the investment outcome. Globally, approximately 20 institutional-quality managers are currently focused on maritime leasing, of which more than half have launched maritime leasing strategies in the post-GFC period (some industry stalwarts, however, have been in business for more than a decade).

We have also noted that an increasing number of managers are now focusing their attention on opportunities created by the push for greater environmental accountability and adapting their investment processes to address investors’ concerns around the IMO and EU’s regulatory requirements, which are now coming into force. A handful of managers have gone even further and are now developing impact strategies to help transform what was once considered an environmentally ‘dirty’ industry.

Given the regulatory pressure that shipping companies are under to retrofit existing fleets—or buy or lease newer ‘green’ ships—the balance of power has shifted to funding partners. Contractual protections for investors are now higher than they have been in decades. Loan-to-value ratios for long-term leases are now lower than they were before the GFC and put options—which allow the leasing manager to sell the vessel to the lessee in the future at a pre-fixed price—are now included more systematically in leasing contracts. Many managers also report that profit-sharing mechanisms are much easier to negotiate with fleet operators than they were in the past.

Mitigating risks: protection is possible

Risks inherent to maritime leasing strategies fall under four key categories:

- Market volatility risk (large swings in asset value prices)

- Risk of non-payment (or delayed payment) on leasing contracts

- Risk of physical damage (to the underlying asset or its equipment)

- Obsolescence risk (associated with legacy engine systems) and broader ESG risks

With respect to the first risk, we would suggest that investors seek to identify managers that actively diversify their exposure by sector, thereby benefiting from the limited correlation between the asset value (and the freight rates) of the different vessel types. In order to further diversify maritime portfolios, investors may wish to focus on strategies that take a staggered approach to lease terms, limiting the percentage that mature in any given year. We also strongly support the use of fixed-price put options to reduce any residual value risk of the asset price upon completion of the contract. Sale and leaseback transactions can also be structured so that a seller’s credit provides first-loss protection in the event of a default.

With regard to the mitigation of credit risks, investors would be advised to make sure that their portfolios focus on a granular mix of high-quality counterparties, for whom the ships represent business-critical assets. Leases can also be constructed as ‘hell or high water’ contracts, which dictate that payments must continue irrespective of any difficulties that the lessee may encounter, usually in relation to the operation of the leased asset. In the case of default, contracts can be constructed to allow recourse to the cargoes onboard, in addition to the ability of taking the vessel back.

To forestall any physical damage to the ship, investors should ensure that their managers employ or engage a technical advisor to monitor the asset and make certain that adequate maintenance standards are strictly enforced. Ships should also be insured against loss of hire, hull damage, and even piracy risks.

Obsolescence risk is perhaps the murkiest risk, in that changing regulatory dynamics are starting to impact the industry—and future-proof technical solutions may not be obvious. Broadly speaking, we would encourage investors to take a keen interest in managers’ approaches to enhancing fuel efficiency in shipping vessels, notably the extent to which ships acquired by their funds would have flexible engine systems: those capable of running on lower-carbon fuels today—and potentially zero-carbon fuels in the future—with sufficient retrofits.

Although shipping has never been a ‘green’ industry, its current transition to new, low-carbon and less polluting fuels (among other ESG requirements) will have a material impact on the way in which the world’s largest commercial transport sector functions. Although the container shipping sector’s stratospheric operating profit margins will likely normalise as pandemic-induced port congestion eases—and supply chain issues abate—the shipping industry’s long-term transformation has only just begun.

For investors, the opportunity to participate in that long-term process has arguably never been more appealing. Managers are now moving with alacrity to help address a huge funding gap in a major industry. Maritime leasing strategies—especially those supported by strong, long-term contracts and predictable cashflows—offer asset owners a meaningful opportunity to support the industry’s decarbonisation strategy while capturing attractive and diversifying returns with good downside protection.

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

English (Global)

English (Global)  Français (France)

Français (France)  Deutsch (DACH)

Deutsch (DACH)  Italiano (Italia)

Italiano (Italia)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)