bfinance insight from:

Ruben Mutsaers

Director

With investor sentiment now appearing to shift in favour of active equity management, as indicated in bfinance’s recent Asset Owner Survey, we ask portfolio design specialist Ruben Mutsaers: what objectives should investors put in place for equity portfolios?

Many institutional investors do put high-level return and/or risk targets in place for their overall equity portfolios in an effort to define and gauge success. Yet the subject is a challenging one. There are different schools of thought on how targets should be developed and applied for a portfolio that may comprise multiple asset managers and span active and passive strategies of various types.

Investors must consider: is the objective meaningful? Is an overall excess return target, such as 1% per year (net of fees) above a benchmark, achievable in view of the investor’s strategy? And how should failure be handled? After all, if a single asset manager does not deliver against their objective then that manager can theoretically be reviewed and replaced with relative ease. Conversely, failure to meet portfolio-level objectives can also place overall strategy—portfolio structure, style choices, the use of active management and more—under intense scrutiny within the organisation.

It is important for investors to have a robust basis for any success metrics they put in place at portfolio level

As such, it is important for investors to have a robust basis for any success metrics they put in place, including ascertaining the real-world achievability of targets and ensuring that portfolios are constructed with those targets in view. Below, we discuss four questions that investors may use when setting out to define goals.

1.Should we have a target for the equity portfolio?

2.Should the targets be relative, absolute or a combination of both?

3.What relative return target is appropriate at portfolio level?

4.How can we construct/refine a portfolio with those targets in mind?

1. SHOULD WE HAVE A TARGET FOR THE EQUITY PORTFOLIO?

Clear, well-founded agreed objectives lie at the heart of strong governance. Targets can, if used sensibly, provide an effective management tool. Targets can drive accountability: if one is going to devote money and time to managing an equity portfolio then the institution should define the benefit that this expense is (and is not) intended to deliver. However, poorly founded targets—or targets whose foundation is not well understood by stakeholders—can be more of a blessing than a curse.

2. SHOULD THE TARGETS BE RELATIVE, ABSOLUTE OR A COMBINATION OF BOTH?

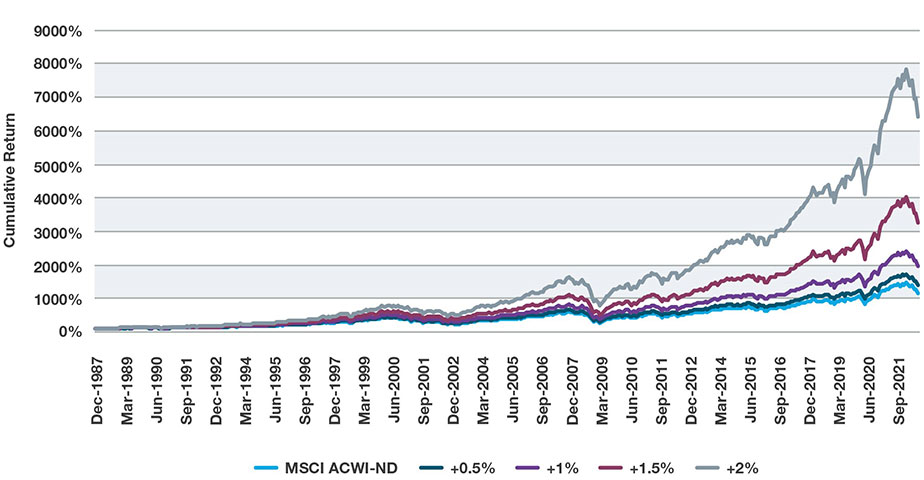

One popular approach for equity portfolios among the asset owners that we work with is the use of a relative return target. This can be framed as ‘[benchmark] plus [X]% net of fees over [long-term period], in [currency] terms’. Small but persistent excess returns can, theoretically at least, deliver massive benefits. The chart below illustrates the desired premium, delivered by the power of compounding.

The impact of generating long-term excess returns versus benchmark

Source: bfinance, Bloomberg

Source: bfinance, Bloomberg

It can also be helpful to specify the risk appetite for the overall equity portfolio in terms of volatility and drawdown. Because public equities are a market-driven asset class, it is most pragmatic to define risk metrics relative to the benchmark. Such targets might include: “improve drawdown profile versus index”, “lower volatility profile than benchmark” or even “risk metrics in line with benchmark”.

A combined approach with multiple objectives can allow for a clearer articulation of intentions, accountability and communication within an investor’s organisation. It is also helpful, in extended periods where one target may not have been achieved, to show how the need to consider other objectives (drawdown risk, for example) may have contributed to that outcome.

3. WHAT EXCESS RETURN TARGET IS APPROPRIATE AT PORTFOLIO LEVEL?

Firstly, our analysis of strategy combinations suggests that it is entirely reasonable to expect excess returns, an improved risk profile or indeed both over the long term—particularly where active managers are used. Yet the question requires careful handling. The appropriate overall excess return target will depend on various factors such as the proportion of passive/enhanced indexation/active management, the styles and geographies used, and whether the organisation is using equity overlays, to name but a few. For example, if a dynamic equity overlay programme is in place, it may be appropriate for the actual equity portfolio to target risk metrics in line with the benchmark; without overlays, an investor may seek a more conservative or even aggressive risk profile than the benchmark.

If the overall tracking error at portfolio level is likely to be small then it is unreasonable for the investor to expect overall excess returns

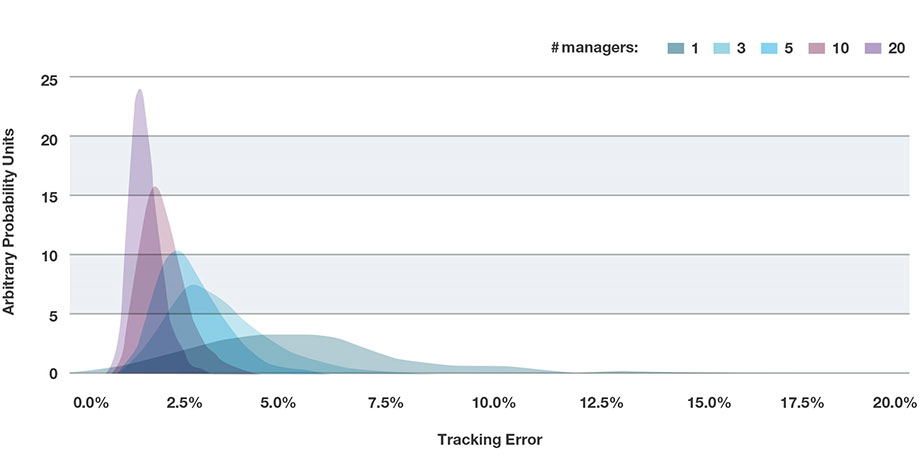

One important consideration—which can sometimes be forgotten—is that active equity portfolios have a tendency to converge to the benchmark when we add more and more asset managers covering the same market. A portfolio of managers that each exhibits a tracking error of 3-4% individually is likely to have a significantly lower tracking error when viewed as a group. And, if the overall tracking error at portfolio level is likely to be small, then it is unreasonable for the investor to expect generous excess returns.

The central limit theorem: tracking error decreases as equity managers are combined in a portfolio

Source: bfinance, eVestment. The eVestment global equity peer group is screened and cleaned to remove less appropriate strategies such sector-specific products, ESG versions of their conventional counterparts, passive products, extremely high tracking error products.

Source: bfinance, eVestment. The eVestment global equity peer group is screened and cleaned to remove less appropriate strategies such sector-specific products, ESG versions of their conventional counterparts, passive products, extremely high tracking error products.

How can this problem be addressed? Firstly, investors can consider setting a Tracking Error budget (and, potentially, an Information Ratio target) to indicate the organisation’s appetite for active positioning. The selected excess return target should be aligned with that TE budget.

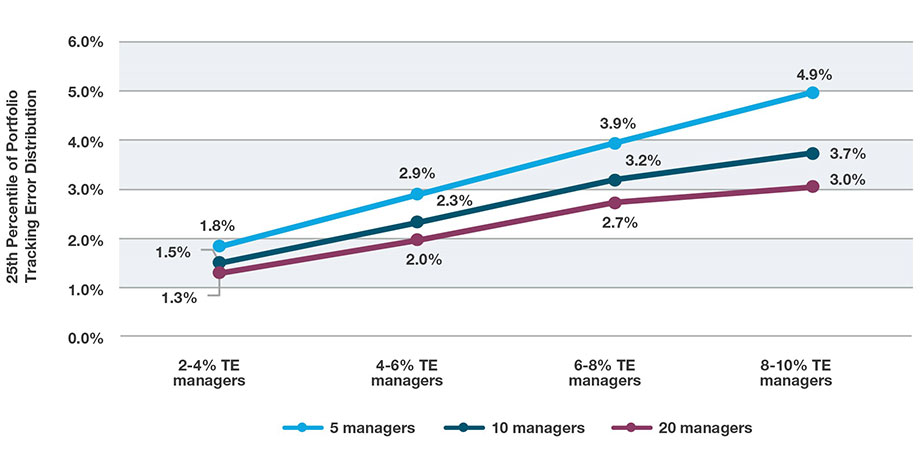

Secondly, investors wanting higher overall excess returns should consider selecting a smaller number of active managers. It is a balancing act: adding more managers reduces the potential for a high tracking error portfolio; manager diversification can, however, improve risk-adjusted return. Third, each of those managers may need to exhibit considerably higher tracking error than the investor would wish to see for the overall portfolio: this point is illustrated in the diagram below.

Tracking error can be elevated by using fewer managers or selecting managers with high tracking error

Source: bfinance, eVestment. The eVestment global equity peer group is screened and cleaned to remove less appropriate strategies such sector-specific products, ESG versions of their conventional counterparts, passive products, extremely high tracking error products.

Source: bfinance, eVestment. The eVestment global equity peer group is screened and cleaned to remove less appropriate strategies such sector-specific products, ESG versions of their conventional counterparts, passive products, extremely high tracking error products.

Fourth, and very usefully, the erosion of tracking error can be mitigated through a conscious effort to appoint a diversified bench of managers with complementary styles. Analysis of active managers in different styles provides compelling data on excess return correlation. Appropriate combinations make it possible to achieve a robust excess return profile, while avoiding excessive dilution of the portfolio’s overall tracking error.

Excess return correlation of active managers in the specified styles, four years to June 2022

Results represent median of composite, gross total return as of June 2022, in USD. Sources: eVestment, bfinance. Manager composites include a representative sample of managers as a proxy for how managers of said style are performing relative to their benchmarks. They do not represent recommendations. Manager style classifications assigned by bfinance.

Results represent median of composite, gross total return as of June 2022, in USD. Sources: eVestment, bfinance. Manager composites include a representative sample of managers as a proxy for how managers of said style are performing relative to their benchmarks. They do not represent recommendations. Manager style classifications assigned by bfinance.

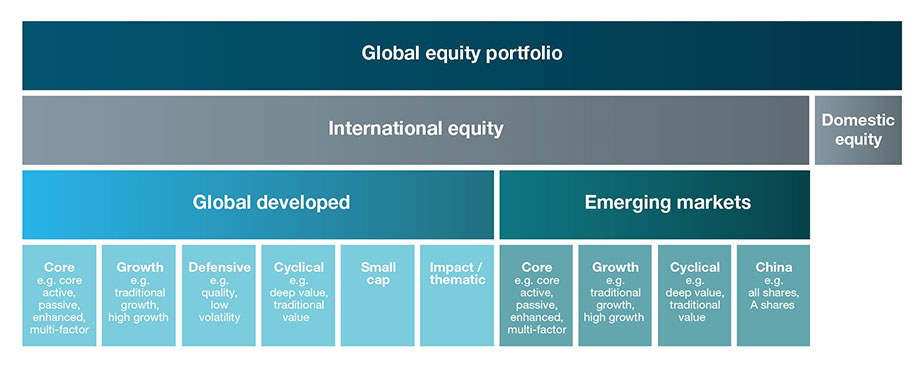

4. HOW SHOULD WE CONSTRUCT EQUITY PORTFOLIOS WITH TARGETS IN MIND?

It helps to start with a ‘base case’ portfolio, which can help the investor form a view on the appropriateness of new or additional portfolio building blocks. That foundation may be global passive equities, a core active global mandate or some combination of appropriate indices. It may not in itself be statistically likely to achieve the investor’s objectives but functions as a pragmatic starting point.

Relative to the base case, an investor can then apply ‘rules of thumb’ for the addition of each new building block. For example:

- Does it have a demonstrable quantitative impact that moves the base-case portfolio towards the investor’s targets?

- Does it have a qualitative role to play, such as delivering on ESG goals?

- Does it tread on the toes of existing allocations (over-diversification)?

- Will it create an unjustified burden on the investor’s resources (over-complexity)?

Through this process, the investor can streamline a portfolio, create stronger alignment with the desired targets and validate the appropriateness of those targets.

Potential portfolio building blocks: an illustrative diagram

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ excess return or risk target that suits all equity investors. When we work with clients on this subject the outcomes are always different. For some, an excess return objective of 1-2% net of fees is entirely valid; in other cases it would not be appropriate. Yet the complexity of the question should not dissuade investors: a rigorous, quantitatively based approach to defining objectives can underpin strong governance of this asset class for many years to come.

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

English (Global)

English (Global)  Français (France)

Français (France)  Deutsch (DACH)

Deutsch (DACH)  Italiano (Italia)

Italiano (Italia)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)