Salvatore Casabona

Salvatore Casabona Head of Complementary Pensions of the national CGIL (Italian General Confederation of Labor), Secretary of Assofondipensione*

More than two decades have passed since the arrival of complementary pension provision in Italy, which brought with it a massive regulatory overhaul. bfinance spoke with Salvatore Casabona to discuss the progress made in the field of Italian pensions.

Established in September 2003, Assofondipensione was founded with the intention of representing the occupational pension funds that were formed after 28 April 1993 across Italy.

Assofondipensione develops proposals and initiatives aimed at improving the activity of the occupational pension fund system, promoting the exchange of information, and evaluates the application aspects of the current legislation.

“We can proudly say that the challenge of creating a modern complementary pension system has been met.

“All this is not the result of randomness or fortunate coincidence, but the result of a commitment to finding new paths and new positions due to the courage and prudence of the directors, the organisational model (the finance function and the fundamental functions introduced by European legislation to protect workers' retirement savings) and the commitment of the advisor companies.”

Q: More than 20 years have passed since the birth of complementary pensions provision in Italy. In light of your experience in this field, could you summarise the path taken so far and what, from your point of view, are the significant improvements achieved in recent years?

We can proudly say that the challenge of creating a modern complementary pension system has been met.

This success is primarily the result of the regulatory framework, shared by the labour partners, put in place by the legislator.

On the lead of the Joint Notice, signed in 2001 by the confederal trade unions and the main employers' associations, the legislator, by enhancing trade union relations and recognising the commitment of the two sides of industry, has built a very complex but at the same time effective regulatory system. In the same way, it has been able to innovate the regulatory framework whenever necessary with regards to the evolution of the public social security system, developments in the financial markets, changes in the production system and changes in the market.

Here I would like to mention the legislative production that begins with the delegated laws, passed through the legislative decrees 124 of 1995 and 252 of 2005, the Ministerial Decrees pertaining to the Conflict-of-Interest regulations, the Requirements of Honourability and Professionalism, and ends with the harmonious incorporation into the Italian legal system of the European Directives IORP2 and SDR. It’s also important to mention the role played by the Supervisory Commission (COVIP) in the proper implementation of the regulations, in building consensus through discussions with the labour and industry partners, and in conversations with the other relevant institutions, first and foremost with the Government and Parliament.

Q: Although complementary pension scheme members have been steadily increasing in recent years, the total number of members continues to be very low as a percentage of the entire pool of Italian workers (especially workers in small and medium-sized enterprises, young people, and women). In your opinion, what are the main improvements that could be made to the complementary pension system in Italy? What are the specific aspects that need attention and change? Are there obstacles or limitations that prevent certain groups of workers from benefiting from these retirement savings tools?

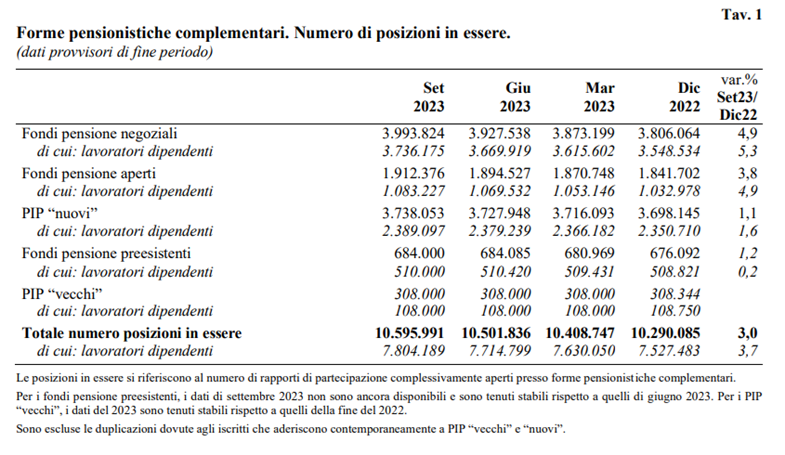

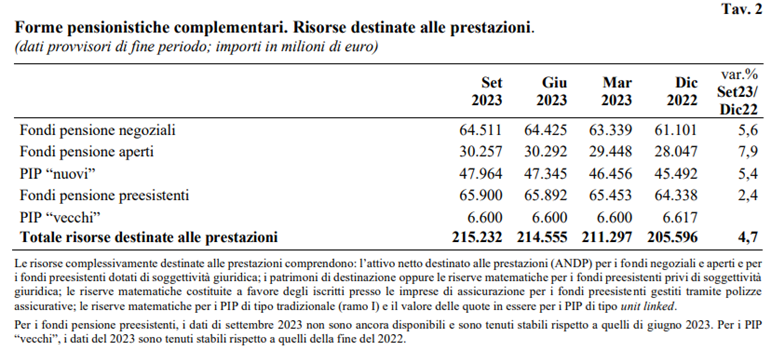

There are 10.6 million members (the outstanding positions) in complementary pension schemes and of those, almost 4 million are members of “negoziali” (contractual) pension funds, while the net assets allocated to benefits amount to a total of €215 billion and of this €64.5 billion is pension savings managed by the “negoziali” pension funds, while the ANDP (Attivo Netto Destinato alle Prestazioni – net assets allocated to benefits) of pre-existing pension funds is around €66 billion.

The data deserves careful consideration to investigate the relationship between members (9 million) and members with adequately financed positions; understand how to correct gender, territory and company size asymmetries; and seek a solution for promoting memberships for employees of small and medium-sized enterprises, where severance pay is still considered by the company as low-cost financing, except to discover that this is not always the case (with the current rate of inflation, it is now much more expensive than before).

We do indeed need an institutional campaign and a semester period to promote membership, but perhaps even more importantly, we need a campaign that enhances the functional relationship between first pillar and second pillar pension schemes.

Similarly, within the principles of freedom and voluntary membership, new ways of promoting membership should be identified, such as institutional protection of the worker who decides to transfer severance pay to the pension fund and experimentation with semi-automatic forms of membership for new hires while leaving the worker with the right to withdraw after a minimum amount of time of membership in the pension fund outlined in their contract.

For the benefit of freedom of adherence, it would be appropriate to provide that the manifestation of will concerning the choice to keep the severance pay at the company be transmitted, for validation, to the inspection service of the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies competent for the territory. I often have meetings at workplaces and record the satisfaction of members with the results achieved and the recognition of the transparency of the system. This is accessible to all through the dedicated part of the pension fund's website, the financial management performance of the fund's sub-funds and the value of their individual position, and to know whether or not payments are regular. Members of the “negoziali” pension funds appreciate the employer's obligation to pay the additional contribution, the low cost of administration and the possibility of choosing the governance of their fund through voting for the Assembly of Delegates, the election of the members of the Board of Directors and the appointment of the Board of Auditors.

Q: What are the advantages and disadvantages of joining a negoziale pension fund versus an individual pension fund? How can negoziali pension funds be structured to maximise benefits for participants?

The financial management of a pension fund has not had a static regulation or a single operating model for quite some time. We started with financial management, characterised by a single sub-fund and today we have a variety of sub-funds, from which the member is called upon to choose. For years, we relied on returns on government bonds to provide silent members and explicit members of prudent sub-funds with returns and guarantees, and we had to change course when the returns in some cases were insufficient for the pension purpose or even negative. We have introduced in recent years the self-assessment questionnaire to enable members to make an informed choice of investment sub-fund. We have implemented IORP 2 and are engaged in the exercise of voting rights shared by many of Asso Fondi Pensione's (hereafter AFP) member pension funds.

We started with purely financial investment and today, the majority of pension funds invest in global financial markets and private markets. I would mention CDP and AFP's Real Economy Project and the role of the Italian Investment Fund, the consortium projects of many funds that have invested in illiquid assets. Finally, we should not underestimate the commitment of many pension funds to choosing investments consistent with the theme of ecological and digital transition. We have dealt with the financial crises of 2008 and 2011, and we have been resilient to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, just as I think we will be able to deal with the financial consequences of the events taking place in the Middle East.

All this is not the result of randomness or fortunate coincidence, but rather the result of a commitment to finding new paths and new positions due to the courage and prudence of the directors, the organisational model (Finance function, Fundamental Functions introduced by European legislation to protect workers' retirement savings) and the commitment of the advisor companies. It should be acknowledged that most of the advisers did not operate on a hit-and-run basis but worked with foresight. The criteria for selecting a manager (ratio of risk taken to expected return, track record, assets under management and costs) used to date have yielded positive results and must be safeguarded. But in the context of the macroeconomic framework and the social aspects of investment, I believe that other criteria must be added, such as the priority commitment to the implementation of ESG principles and the impact of the investment on the Italian economy, on domestic enterprise, and on the creation of new employment. Reasoning in terms of the creation of domestic employment and the assumption of ESG criteria in the selection of the financial manager probably means forcing advisers to measure themselves against an evolutionary context of this magnitude (and not everyone is ready), while allowing the entry of new players as competitors/actors in the financial management of a pension fund.

Q: You have been an adviser and president of negoziali pension funds for quite some years, and in this capacity you have interfaced with both managers and financial advisers, also going through complex moments in the financial markets. What do you think the role of advisers for negoziali pension funds should be, particularly on the clear distinction between the different tasks that a financial adviser must be able to offer as is already the case in international markets, and whether you think the Italian market is able to accommodate this distinction already present in other markets?

International best practices call for dividing the responsibilities of the advisers supporting the bodies in two macro areas: defining strategic asset allocation consistent with the fund’s investment policy and selecting managers. The decision to have dual financial advisers is an option that many funds have incorporated into their organisational model. Having two advisers that complement each other allows for better process transparency and reduced risk of conflict of interest, and better enables the directors of the pension fund to exercise the role that the IORP2 directive has assigned to them. As with all organisational processes, the pioneer funds move first while there are funds that wait to understand the evolution of the issue. For these reasons, I consider the separation of responsibilities an inescapable and extremely positive process for transparent decision-making.

Whether I think the Italian market can grasp the positivity of this distinction, I answer with strong conviction, yes. The market demands it, it is in the interest of advisors, it is consistent with the most recent European directives, and it will strengthen the transparency of decision-making processes of boards and give more awareness to members.

Q: You have been an adviser and president of negoziali pension funds for quite some years, and in this capacity you have interfaced with both managers and financial advisers, also going through complex moments in the financial markets. What do you think the role of advisers for negoziali pension funds should be, particularly on the clear distinction between the different tasks that a financial adviser must be able to offer as is already the case in international markets, and whether you think the Italian market is able to accommodate this distinction already present in other markets?

The challenge of the near future concerns the issues of investment the real and sustainable econmy, risk control and the exercise of voting rights seen as tools that can achieve a single goal. Workers' savings serve to produce security, sustainability, shared transition, strengthening of the production system, creation of good jobs, and can activate that virtuous path that goes by the name of economic democracy. The spirit and letter of the norm, the vision of the founding sources and the pressures of the members direct the actions of pension funds toward a new perspective within which advisers will be called upon to meet new challenges and measure themselves with new approaches of investment policy, increasingly consistent with the political debate on the mechanisms of economic, environmental and digital transition.

The new financial management thus characterised is action in the majority of pension funds, and we are working to associate all pension funds in this perspective, from taking on ESG challenges to integrating them into risk management.

Q: What future trends or developments do you foresee in the supplementary pension sector in Italy? For example, are new ESG (environmental, social and governance) investment approaches gaining importance in the sector? What could be the implications for negotiated pension funds? Net of the indications that the new European legislation is producing in this area, do you think now is the time to see an increase in engagement activities by pension funds on environmental and social sustainability issues?

ESG presents another evolving scenario in financial management that will force advisers to grapple with new issues and the implementation of the European SRD2 directive and the COVIP regulation on the transparency of shareholder engagement policy.

It is a new and fascinating challenge, but at the same time fraught with difficulties, as pension fund administrators are required clearly outline their commitment policy as shareholders in European listed companies; to give explanations if a commitment policy has not been adopted; and to account for the consistency of the equity investment strategy and the expected return with the fund's investment policy.

In conclusion, it is a matter of bringing to life the present expectation of the 1991 and 1992 Government Unions and Social Partners Protocols to use workers' savings to implement a contractual welfare system (Social Security, Supplementary Health Care and Bilaterality) that can improve their quality of life and initiate a process of economic democracy that the country and workers need.

*Salvatore Casabona is also Board member of Previdenza Cooperativa (Negotiated Pension Fund for cooperative members and employees) and Fondapi (Pension Fund for Small and Medium Enterprises), Contract Lecturer at Luiss business school (Contractual Welfare) and La Sapienza University (Complementary Provision).

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

English (Global)

English (Global)  Français (France)

Français (France)  Deutsch (DACH)

Deutsch (DACH)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  English (Canada)

English (Canada)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)