bfinance insight from:

Martha Brindle

Senior Director, Equity

Oliver Wade

Associate, Investment Content

Quality-oriented equity strategies have long been a favourite among institutional investors—but quality indices have struggled to gain traction. When benchmarking style-specific active strategies, asset managers and practitioners often turn to value or growth indices but will rarely employ a quality index to assess a track record. bfinance asks: why is this the case? And how should allocators think about ‘quality investing’ in the wake of recent performance challenges?

The quality question

‘Quality’ strategies proved a highly popular ‘style’ choice in active equity manager selection throughout the 2010’s and early 2020’s. While sentiment towards value investing soured and investors grappled with the risk that a historically long, growth-driven bull market would come to an end, quality offered the best of both worlds: a growth-leaning tilt that captured the tech surge, yet with a reputation for resilience during downturns.

Notably, a quality foundation is common across styles. In value strategies, balance sheet strength contributes towards value trap avoidance.an help to avoid value traps. In growth approaches, quality signals—such as durable competitive advantage—support sustainable earnings growth projections. Yet despite this broad investor appeal, quality indices never became a go-to tool for benchmarking. What explains this disconnect? To a large extent, allocators may take inspirationa lead from their asset managers, as even those managers with an explicit quality focus rarely use quality indices as a reference point—preferring instead to use broad market indices. This is a notable contrast with value and growth, which are widely used as a secondary style benchmark—in some cases (particularly in the US) even a primary benchmark—for relevant active strategies.

But why? The argument often given is that quality indices do not capture the myriad ways in which active managers typically define and seek quality. MSCI’s Quality factor, for example, is built on three financial metrics—return on equity (ROE), earnings variability, and debt-to-equity ratio. While these are useful indicators, they are backwards-looking and fail to account for forward-looking elements, such as threat of competitive disruption, management quality, and long-term sustainability of earnings—factors that will (almost without exception) be considered by active managers in determining quality. Practitioners may also assert a more disciplined approach to valuation, helping to counteract one of the key risks in quality investing—exposure to ‘high quality’ but over-valued stocks. Moreover, it’s worth considering sector biases in quality indices: their overweight stance in IT, healthcare, and communication services can lead to return patterns that are more dependent on sector trends than on the quality factor itself.

Does quality equals growth?

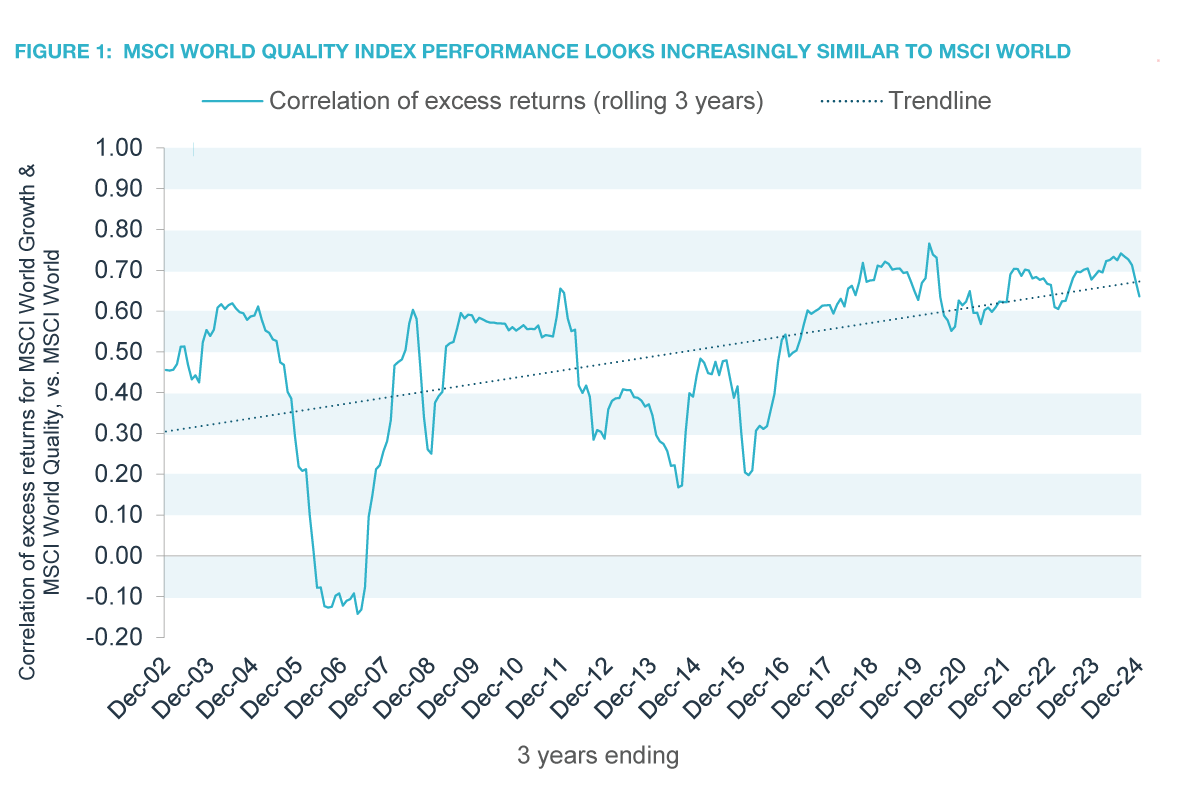

We have observed—both through return patterns and holdings similarity—that quality indices have become increasingly ‘connected’ to growth indices. In Figure 1 (below), we show rolling correlations between the excess returns of the MSCI World Growth and MSCI World Quality versus the MSCI World index. These averaged less than 0.4 for the periods ending 2011-2016 and fluctuated in that time. Since 2018, the correlation has been higher—above 0.6—and stickier.

Source: bfinance, eVestment, USD net index returns to December 2024. Indices used: MSCI World Quality, MSCI World Growth, MSCI World. Calculated on a monthly basis.

As of 28 February 2025, 7 of the top 10 constituents of the MSCI World Quality index are also among the top 10 of the MSCI World Growth index—including Alphabet, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and NVIDIA. Such data suggests that quality indices have increasingly behaved as a subset of growth rather than representing a truly distinct style.

The big question: has quality lacked resilience?

Quality is perceived as a defensive style of equity investing, offering protection in drawdowns. While this holds over time and through longer periods of assessment, recent performance indicates a different story, as shown in Figure 2.

Source: Source: bfinance, eVestment, USD net index returns to December 2024. Calculated on a monthly basis.

A downside capture ratio above 100% can be interpreted as “declined by more than the market in a downturn”; one would therefore expect the defensiveness of quality to show through with downside capture below 100%. However, recent three-year periods show MSCI World Quality index performing worse than the market during drawdowns. Figure 2 shows that the downside capture of the MSCI World Quality index is notably higher (meaning weaker) in recent rolling three-year periods than in the past. This suggests the quality index’s resilience is evidently harder to validate in recent markets—in fact, it looks strikingly similar to the growth index.

The MSCI World drawdown over calendar 2022 (-18% in USD net terms) saw the MSCI World Quality fall even further (-22%). This counterintuitive lack of downside protection in the quality index was due to the unusual nature of the 2022 market decline, in which the Energy sector was the only sector to generate positive returns and traditionally defensive ‘long duration’ stocks derated amid rising interest rates, inflation and recessionary fears. Contrast this downturn with the Covid crash: this unusual market decline saw technology stocks heavily insulated due to strong lockdown-related demand for digital services, benefiting indices (including the MSCI World Quality) with overweight positions to the sector. Nuance is needed in assessing performance during these environments: there is some truth in the adage that ‘this time, it is different’. Market downturns are not created equally, and we should not expect the same trends to play out each and every time.

Understanding active quality manager performance

The diversity of approaches within the quality universe makes the discussion around benchmark selection still more complex. The heterogeneity is such that we at bfinance have had to answer with three distinct active manager peer groups for performance comparison: Classic Quality, Quality Value, and Quality Growth (see Defensive Equities and Market Downturns for more details). More straightforward, perhaps, to stick with the standard market benchmark as an appropriate yardstick, though adjusting expectations based on the nuance of each group.

Applying these insights in manager selection

Given the limitations of quality indices, how should investors implement quality investing in practice? A more tailored approach is required, particularly in manager selection. At bfinance, we recommend a three-step framework to evaluate quality-focused managers:

- Investment Philosophy and Process: Understanding how a manager defines and applies quality is essential. This requires assessing not only the metrics they use but also their ability to incorporate qualitative factors, forward-looking views, and risk management into their approach.

- Portfolio Characteristics: Rather than focusing on index comparisons, it is more insightful to examine the fundamental attributes of a manager’s portfolio. Does the portfolio exhibit stronger profitability, lower leverage, and more stable earnings than the market? Are these characteristics consistent over time?

- Track Record and Risk Profile: Instead of benchmarking against a quality index, a better approach is to analyse a manager’s return profile against the broader market, focusing on downside protection, drawdown recovery, and resilience in different market environments.

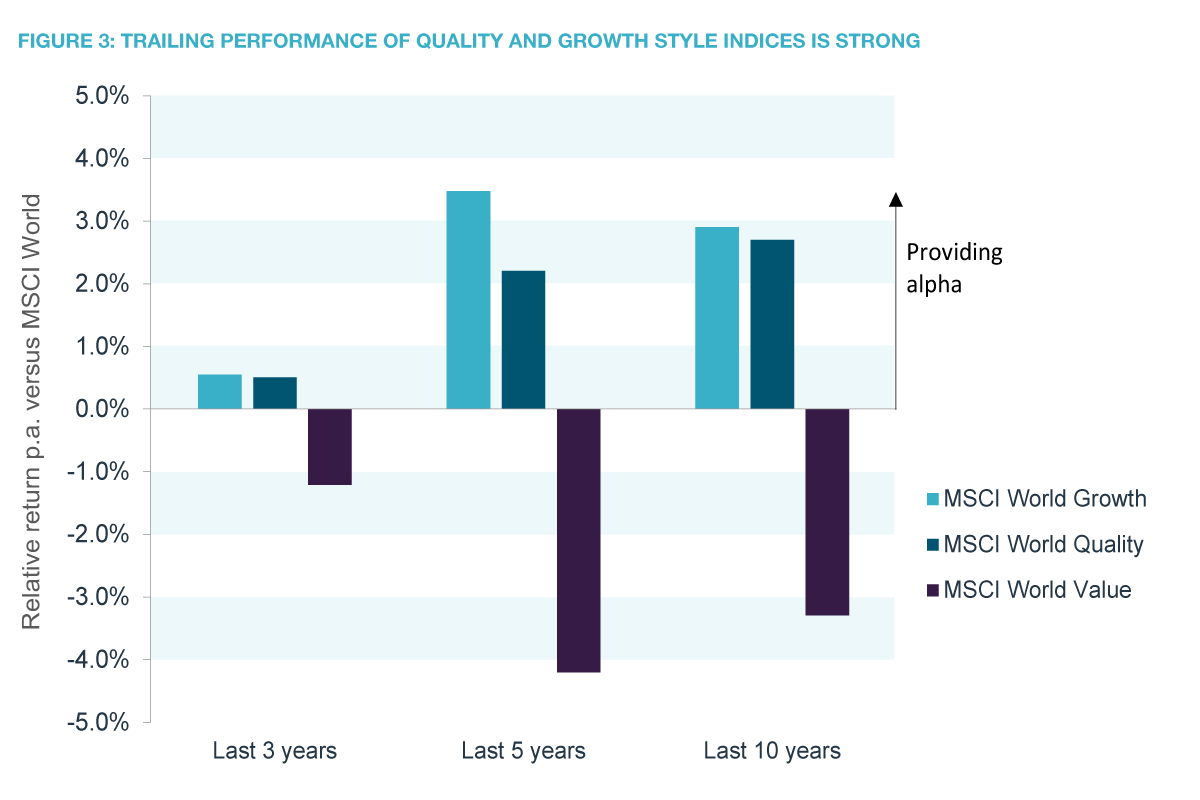

Source: bfinance, eVestment, net index returns to December 2024.

A recent bfinance quality equity search demonstrated the importance of this approach. The analysis revealed that while some managers had struggled to beat the MSCI Quality Index, they had delivered superior downside protection and more stable returns over time—characteristics more aligned with what investors seek in quality strategies. By focusing on real-world quality outcomes rather than index comparisons, investors can make better-informed decisions about which managers align with their objectives.

Rethinking quality measurement and implementation

While quality indices offer a useful reference point, they are not a perfect tool for benchmarking quality strategies. Their overlap with growth, reliance on backward-looking metrics, sector biases, and inconsistent defensiveness make them a less effective measure of quality investing than commonly assumed.

For investors seeking true quality exposure, a more nuanced approach is required. This involves focusing on how quality is defined and implemented in practice, rather than relying on index-based benchmarks. By evaluating managers through a broader set of metrics—including fundamental quality attributes, downside protection, and performance across market cycles—investors can build quality allocations that more effectively meet their long-term goals.

Rather than asking whether quality indices are useful, the more pertinent question is: what does quality truly mean, and how can investors best capture it?

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

English (Global)

English (Global)  Français (France)

Français (France)  Deutsch (DACH)

Deutsch (DACH)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  English (Canada)

English (Canada)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)