bfinance insight from:

Kathryn Saklatvala

Senior Director, Head of Investment Content

The past two years have seen huge growth in the availability of private market strategies that offer some degree of in-built liquidity, such as open-ended funds and diversified multi-manager strategies (the latter are discussed in our recently published white paper – Rise of the Allocators). Open-ended private market funds achieve liquidity in different ways, with very different potential outcomes. In this article, the bfinance Private Debt team takes a closer look at open-ended Private Credit with new data on strategy types and liquidity mechanisms.

This article is part of a Liquid Private Markets series. Read Part 2 (Infrastructure) here.

While open-ended strategies for investing in private Real Estate are relatively well established, recent years have seen the emergence of an extensive roster of such funds in Infrastructure and Private Debt, as well as a nascent group in Private Equity.

The “explosive growth” of open-ended Infrastructure funds, for example, was tracked in an end-2022 report from bfinance/Infrastructure Investor: the volume of assets raised by these vehicles increased by 64% between December 2020 and June 2022, while H1 2022 saw a record number of fund launches (20). The open-ended Private Debt fund landscape has seen a similarly seismic expansion: among the 40-plus open-ended funds now available to institutional (and in many cases wealth/retail) clients in this asset class, approximately four fifths of them have been launched within the past two years. As a group, open-ended private debt strategies are now in vigorous fundraising mode: overall, we estimate that they are only about 10-15% of the way to their AuM targets. The trend also spans different geographies, with open-ended Private Debt funds predominantly focusing on the US market while open-ended infrastructure funds lean towards Europe.

The attractions and dangers of liquidity

Open-ended funds can solve two specific issues that investors have with private debt: the potential need for liquidity and the challenge of remaining fully invested over time. Some of the investors involved may have practical ongoing liquidity requirements, such as wealth managers whose underlying client commitments could vary through time. Others may find it easier from the perspective of their risk management or regulatory structure to be in a fund that has inbuilt liquidity provisions, even if these are not actually expected to be utilised: various pension funds and insurers may find that this is the case. When it comes to staying invested, asset owners with lean in-house teams may be particularly interested in the resourcing implications: closed-end private market strategies create a burden on the investor, who needs to constantly monitor and reinvest returned capital to create a consistent level of exposure, and this workload can be particularly onerous in the case of Private Credit due to the pace of interest payments and redemptions; open-ended strategies, on the other hand, take that recycling problem off the investor’s plate (see Tackling the Committed Capital Conundrum).

Notwithstanding these prima-facie benefits, last year delivered a stern reminder of what can happen to open-ended strategies when their liquidity is tested. The deleterious consequences were most visible among open-ended real estate funds – particularly Core/Core+ funds in North America and Europe with high retail investor exposure or with pension fund investors that were overexposed to real estate (due to falling public market valuations) or vulnerable to the UK Gilt sell-off. bfinance estimate that there is over $50 billion of capital in redemption queues from such funds in the two regions.

Liquidity mechanisms in focus

Fundamentally, offering liquidity in private market investment vehicles where the underlying assets are not themselves, liquid will always come with inherent tensions, trade-offs and perhaps even conflicts of interest. Investors must consider this with care when selecting a strategy. Not all open-ended Private Credit fund managers ‘square the circle’—reconcile liquidity with illiquidity—in the same way. These funds allow redemptions, usually capped at around 5% of fund size each quarter and they use a range of mechanisms to support that liquidity.

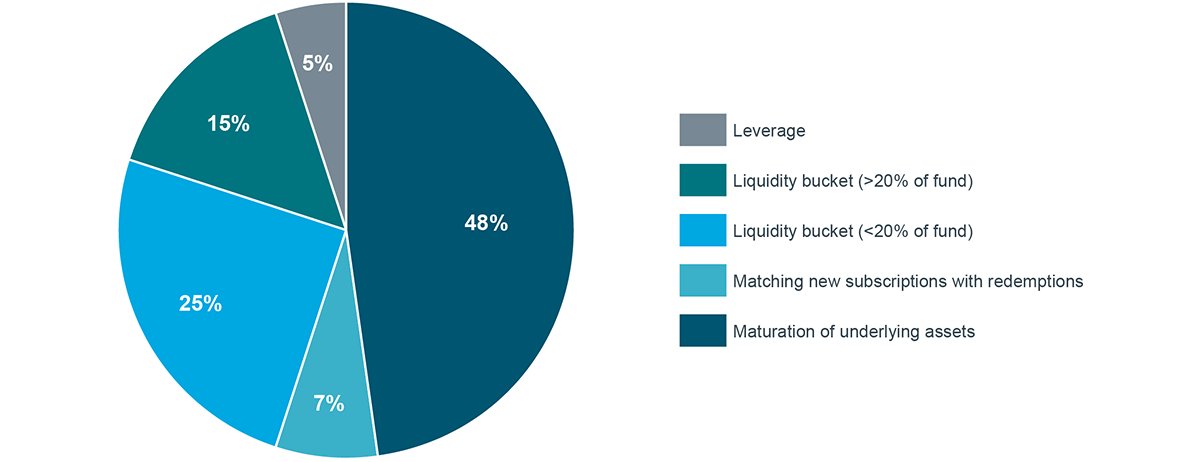

Primary liquidity mechanism of open-ended private debt funds

Source: bfinance, 40 open-end private debt strategies from 38 managers

Firstly, all private market strategies have a degree of ‘natural’ liquidity that depends on the specific investments themselves, such as the coupon payments or other income/yields thrown off during the lifecycle of the investment and the duration for which investments are held (and whether that is inherent to the structure, such as the maturation of a loan, or dependent on some sort of exit). In the case of Private Credit, loans typically have a five-year term and realistically tend to be paid off in four, so nearly a quarter of a mature portfolio will tend to self-liquidate each year; in essence, this asset class does benefit from a higher volume of inherent liquidity than many other private market sectors. Another form of ‘natural’ liquidity might come in the form of new investors subscribing (or waiting to subscribe) to the fund. Overall, more than half of current open-ended private debt funds are relying purely on these natural mechanisms to provide the necessary liquidity for their strategy, as shown in the chart above.

Yet this natural liquidity may be insufficient or, more accurately, may not be large enough to avoid conflicts of interest between the LPs who leave and those who remain. If we assume a gate of 5% per quarter, and therefore total maximum redemptions of 20% over the course of the year, exits could absorb the entirety of the natural liquidity generated in a given year, while future subscriptions are of course uncertain. This creates a problem: it is important that the fund keeps on re-investing so that the next crop of maturities is sown and the remaining/future LPs are not left behind with a poorly constructed rump of a portfolio. A decision to use an open-ended strategy that depends purely on natural liquidity must include very careful consideration of the existing LP base and the extent to which their interests are aligned. It can be helpful to ensure that the underlying investors have common ground (hence institutional investors might prefer to avoid strategies with a significant portion of wealth/retail assets), but excessive similarities might mean that all investors head for the exit doors at the same time: UK corporate pension funds’ behaviour amid the LDI crisis of 2022 represents, perhaps, a case in point.

As such, investors might want to consider strategies with additional liquidity mechanisms in play, the most popular being a certain amount of exposure to public market investments – chiefly short duration bonds or broadly syndicated loans. Some 40% of open-end Private Debt funds use such ‘liquidity buckets’. In most cases they represent less than one fifth of total assets, providing a reasonable liquidity buffer in stable conditions, although large withdrawal requests could still pose difficulties. A significant minority of strategies, however, have even larger allocations (>20%) and these may offer more frequent and reliable liquidity windows (e.g. monthly).

While a sizeable liquidity bucket may mean that redemption requests can be serviced without affecting the Private Credit investments or impeding the fund’s ability to reinvest in new loans, the introduction of liquid exposures does alter the risk/return profile of the strategy, potentially introducing significantly higher volatility, lower return expectations and weaker investor protections. An investor could theoretically make a larger allocation to this type of fund in order to deliver a desired level of allocation to private credit alongside liquid exposures.

Finally, 5% of open-end Private Debt funds primarily rely on a credit facility—fund-level leverage, in other words—to meet redemption requests beyond what the fund would comfortably tolerate. This approach can effectively smooth out cashflows in a relatively stable environment, and preserves the Private Credit characteristics of a fund, but large withdrawals could rapidly cause the fund to become over-leveraged and not all investors are willing to tolerate the additional credit risk exposure involved.

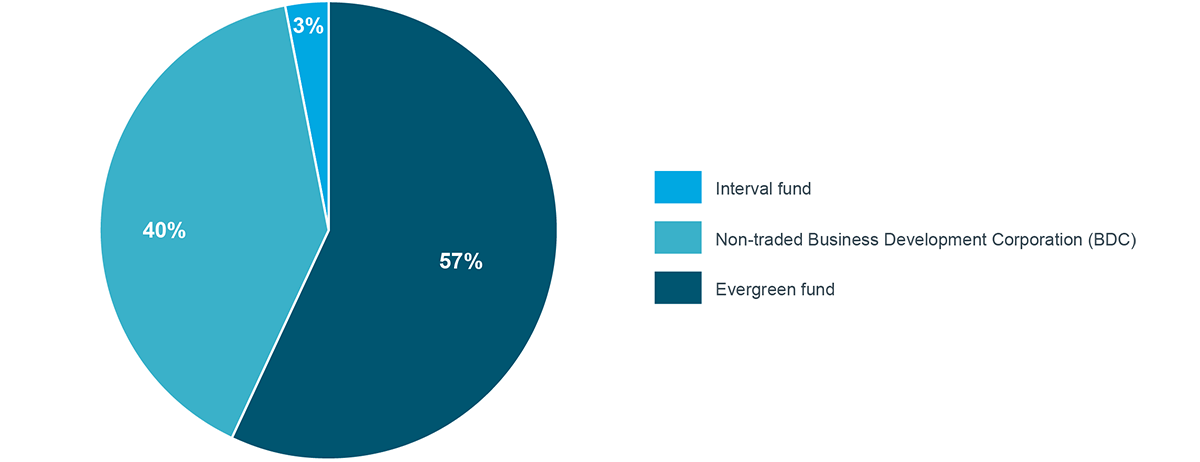

The approach to liquidity is also related, to some degree, to the fund’s structure. While ‘evergreen’ funds (57% of vehicles) are more likely to use liquidity buckets, Business Development Corporations (40% of vehicles) are more likely to rely on the use of leverage and underlying loan maturities.

Structure of open-ended private debt funds

Source: bfinance, 40 open-end private debt strategies from 38 managers

Ultimately, the rapid expansion of open-ended strategies across the private market spectrum represents a useful and positive development for those investors who find this strategy type to be a better fit for their needs than a closed-ended fund. Yet it is crucial to take a care when scrutinising the liquidity promises of these vehicles, the natural liquidity provided by their underlying assets, their additional liquidity provisions and their underlying LP base.

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

English (Global)

English (Global)  Deutsch (DACH)

Deutsch (DACH)  Italiano (Italia)

Italiano (Italia)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  English (Canada)

English (Canada)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)