bfinance insight from:

Frans Verhaar

Senior Director, Client Consulting Netherlands & Denmark

Janessa Valo

Senior Associate, Client Consulting Nordics

Nordic and Dutch investors are shifting the ESG agenda decisively towards ‘impact’ – whether that takes the form of measuring non-financial portfolio outcomes ex post or targeting social and environmental objectives ex ante.

The wider effects generated through investment, both negative (e.g. carbon emissions) and positive (e.g. job creation), have moved from sideshow to centre stage. Bfinance’s recent ESG Asset Owner Survey contained several key indicators suggesting a growing focus on impact among financially-focused long-term investors, including pension funds, insurers and endowments. These data points include the increasingly widespread practice of mapping portfolios against the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or engaging in other forms of impact reporting; the rising proportion of investors measuring portfolio carbon emissions; and the growing popularity of both impact investing and ESG-related thematic investing across a range of asset classes.

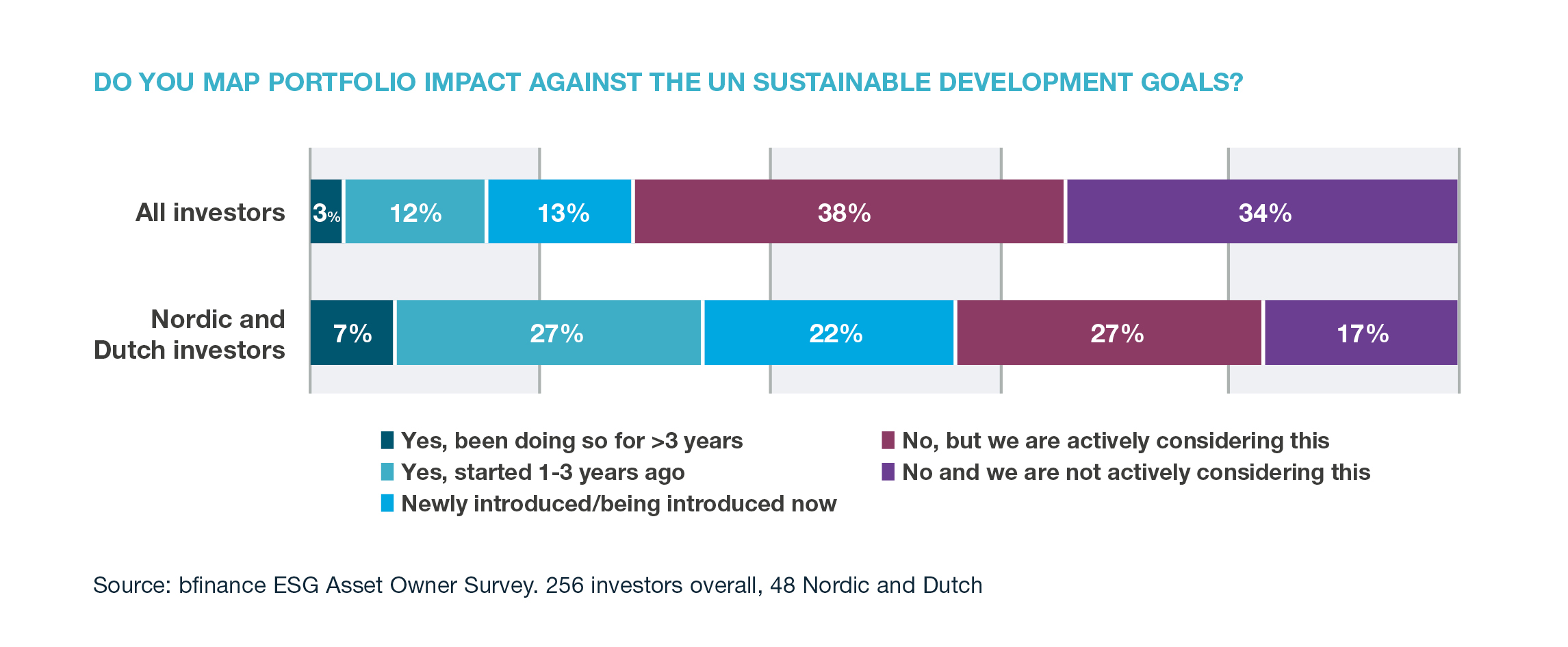

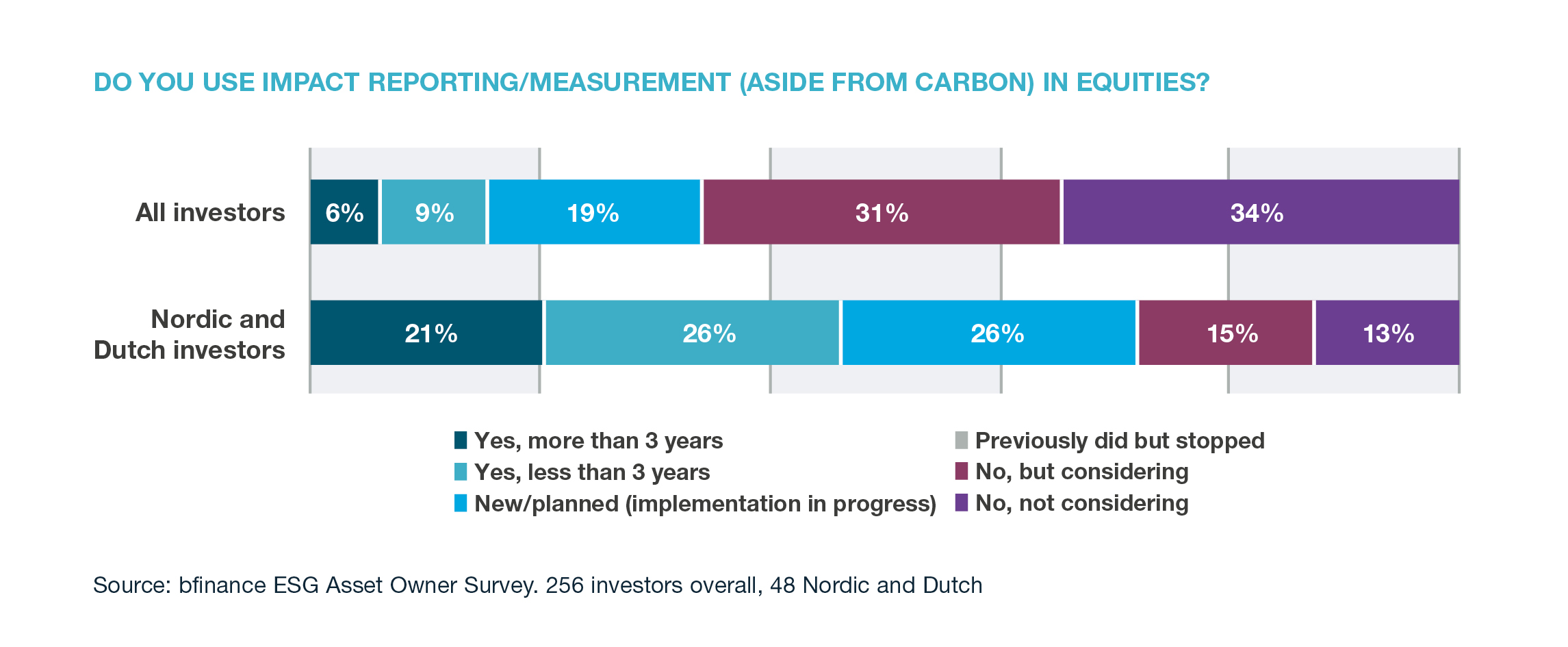

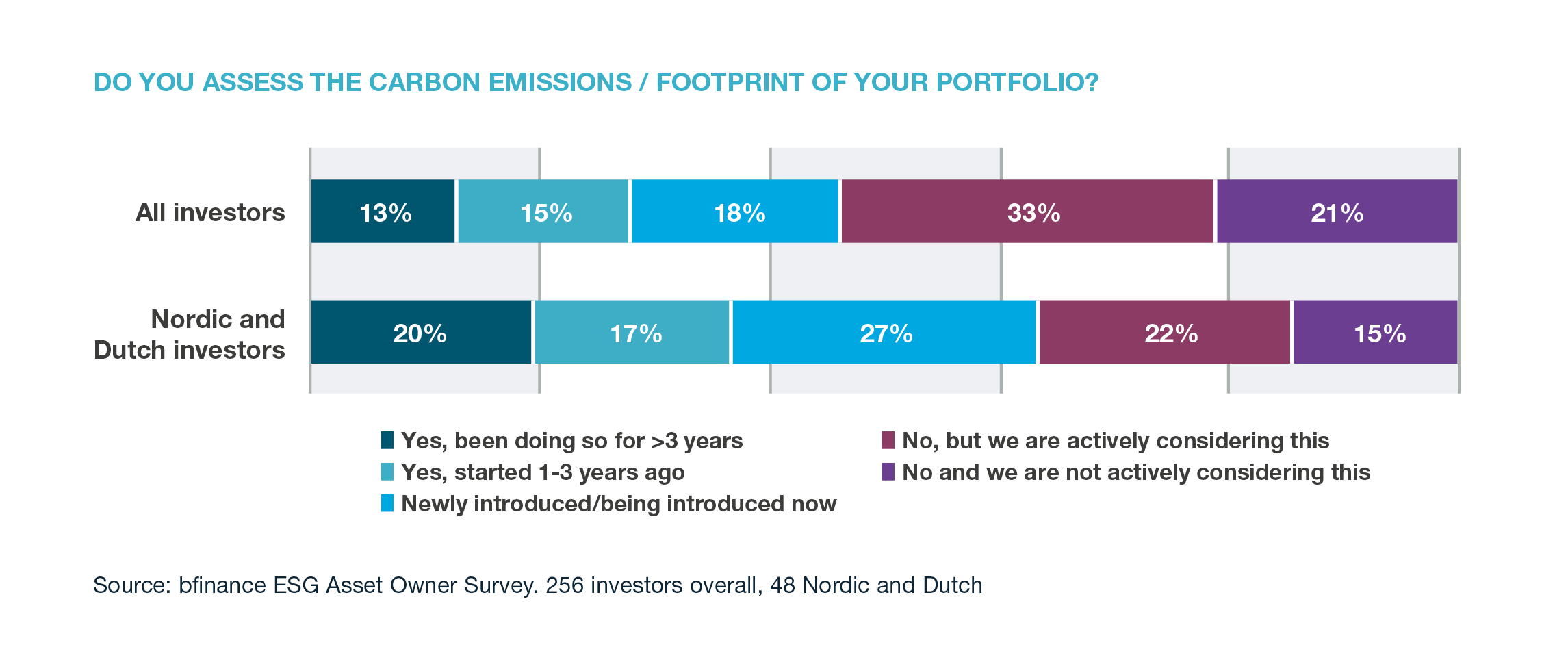

On almost all relevant metrics, Nordic and Dutch investors are leading the way – not just globally, but also in a European context. For example, twice as many investors in this region perform SDG mapping in comparison with their global peers (56% versus 28%). An even bigger difference emerges for impact reporting (not including carbon) in equities: 73% of Nordic and Dutch investors versus 34% globally. The gap is narrower when it comes to carbon reporting, due in part to the wider political and regulatory emphasis on this subject: 64% of investors in the Nordic and Dutch regions assess overall portfolio carbon emissions versus 46% of global investors.

The world appears to be following where investors in this part of Europe lead.

As has been the case with the adoption of wider ESG agendas over the longer term, the world appears to be following where investors in this part of Europe lead. For example, 38% of investors globally are actively considering SDG mapping, while an additional 33% may soon start measuring portfolio carbon emissions. In search of more insight on current innovations, we recently spoke with a range of Nordic and Dutch investors at different stages of their impact journeys to gain a deeper understanding of their different practices, ongoing developments and notable challenges.

SDG mapping becomes mainstream

Investors in the Nordic and Dutch regions have so far adopted SDG mapping at double the global rate, although that gap appears to be narrowing based on the very high figure actively considering doing so – as shown below. Yet what does this mean in practice?

The most common approach involves picking a selection of goals rather than using all 17. These shortlists vary considerably, although Goal 13 (Climate Action) features in virtually all cases. There are different pathways to SDG selection: Some have focused on objectives that relate to the institution’s investment portfolio as well as its corporate agenda, such as the path chosen by Alecta in Sweden. “We identified a number of SDGs that really fit our organisation, which we can work with both internally as a pension fund and also in our investments,” explains Head of Responsible Investment Peter Lööw; Alecta’s four goals are: 13, 5 (Gender Equality), 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and 11 (Sustainable Cities). In those cases where a parent entity or sponsor organisation also has a wider business remit, such as insurance, its goals may reflect that business agenda as well as the priorities of its investment arm. We note interesting examples of pension funds surveying their members to identify which SDGs they’re most concerned about; in other cases, investors have selected impact goals without SDGs in mind and then subsequently translated them into the UN framework.

The last example perhaps demonstrates the primary benefits of the SDGs: although broad and non-prescriptive in terms of their specific metrics, they represent a fantastic communication tool to convey impact issues to a range of audiences. They also serve as a rallying cry – a banner under which investors can come together and collaborate on impact issues. “I think it is important for pension funds to coordinate on SDGs, just as we coordinate on engagement and voting,” says Pieter van der Ende, Investment Manager at Rabobank Pensioenfonds.

Impact measurement: the new frontier

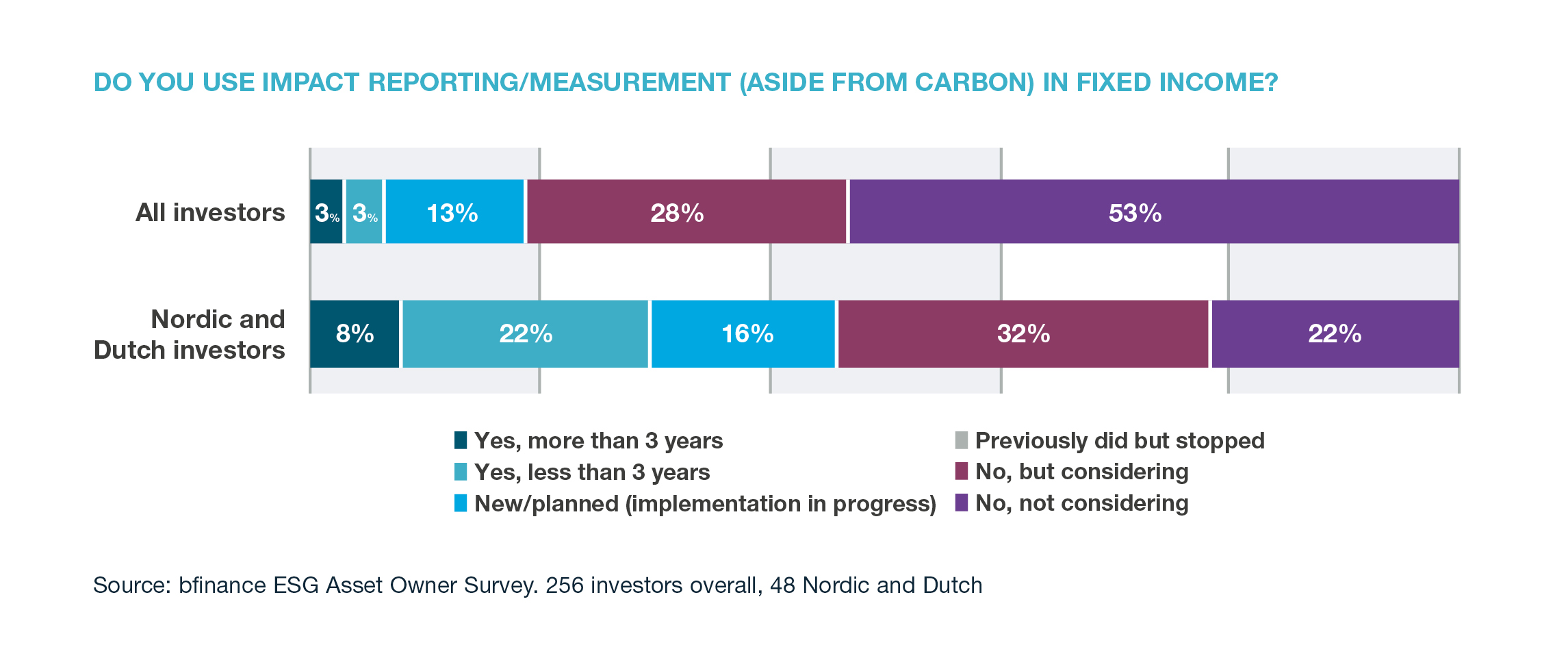

SDG mapping should be viewed as just one aspect of a broader trend: the shift towards calculating non-financial outcomes that relate to investments. As shown in the charts below, Nordic and Dutch investors tend to be further ahead on the subject of impact reporting for both equities and fixed income. Carbon was specifically excluded from this question and is addressed separately below.

Impact reporting is most advanced in equities where data availability is strongest. “For impact reporting, we’re focusing on equities first since that’s where we can access the most data, and then will be looking at other asset classes as well,” says Niina Arkko, Responsible Investment Analyst at Ilmarinen Mutual Pension Insurance Co., which currently has a target in the direct equity portfolio for a 12% revenue share contribution to the SDGs. Fixed income is a little further behind, with 46% of Nordic and Dutch investors currently doing impact reporting in bonds (versus 19% globally) and 32% considering it.

Looking towards private assets, the potential impact can be high but obtaining appropriate data is even more challenging. In real assets (real estate and/or infrastructure), 39% of Nordic and Dutch investors conduct impact reporting in comparison with 22% of their global peers. In private equity, meanwhile, we see almost no difference, with 20% of investors both in this region and globally undertaking impact reporting.

It is interesting, perhaps, to observe that the theme of impact reporting is more advanced in fixed income than in real assets in the Nordic and Dutch region – but the opposite is true globally. In part, this fact reflects the region’s significantly higher usage of specific fixed income products with a measurable impact such as green bonds, sustainable bonds and social bonds.

Peter Lööw,

Peter Lööw,Head of Responsible Investment, Alecta

A couple of years ago I thought impact reporting would be very simple: I expected that we’d get the impact reporting, aggregate it and present it. In reality, the experience was the complete opposite: the indicators are so different that we couldn’t really compare them. If you look at sustainable and green bonds, for example, the reporting is often not in a format that we can aggregate. We’re now working on efforts to harmonise the reporting, and other entities are trying to encourage that harmonisation too.

Impact reporting is, to say the least, an extremely challenging topic. “There isn’t a common language for measuring impact,” observed Jos Gijsbers, Senior Portfolio Manager at Dutch insurance company ASR Nederland N.V. (Asset Management). “You see that everyone is measuring their own impact with different metrics and you can’t compare them.” This is true for asset managers across a single asset class; other asset classes add yet more diversity. Although investors tend to want only a handful of metrics, managers may provide hundreds of different indicators. Even once an appropriate collection of metrics has been established, investors may struggle to calibrate the trade-offs between impacts in different parts of the portfolio in the absence of a common currency that links them. Carbon emissions can be priced – and the value of a tonne of carbon saved is clearly understood irrespective of asset class and strategy – but that simplicity and convertibility is absent in other areas.

The (big) business of impact data

With an urgent need for better information – more of it, as well as more consistency – we see rapid evolution among data providers, index providers, asset managers and investees/issuers seeking to service demand. Here, again, we believe it’s important to distinguish between the subject of carbon emissions (discussed further below) and other types of outcomes.

Investors broadly welcome the range of initiatives being undertaken on a national, supranational or industry/association level to encourage better provision and standardisation of data. Most prominently, the EU sustainable finance plan is working towards a more prescriptive approach to company reporting. Interesting local examples have emerged in Northern Europe, such as the Nordic Public Sector Investors Group, which now releases an annual position paper on green bonds impact reporting, with a view to improving harmonisation.

When it comes to obtaining and crunching data, investors can acquire their own tools with which to screen portfolios and/or use reports from external asset managers. Large firms have sought to build or buy capability during recent years, as illustrated by the acquisition of companies like Sustainalytics, Vigeo Eiris and TruCost. Today, new companies and innovative approaches continue to emerge. “We are participating in a pilot with a company that assesses companies’ SDG impact – positive and negative – using artificial intelligence,” says Gijsbers. “There’s so much information in the world now and it’s important to form an independent view rather than relying on company reporting.”

Niina Arkko,

Niina Arkko,Responsible Investment Analyst, Ilmarinen Mutual Pension Insurance Company

We use different data providers for different areas. At the moment we have three providers for carbon data (two in equities, one in real estate), one provider for SDGs, one on treaty non-violation, one for ESG ratings and one for proxy voting. We have also been discussing with various service providers for the impact side, separately from the SDG provider. This creates homework for us in terms of consistency and how we utilise all the data from different providers.

Investors are extremely aware of the shortcomings of the data and analysis that they’re currently able to access in this space. Although the picture is a work in progress, improvements are being made. Reporting transparency is a real challenge when it comes to gauging social impact, especially when considering the supply chains that companies use, but it is increasing. SDG and impact data providers are now doing better at netting out ‘negative’ social and environmental impacts against the ‘positive’, although data tends to be stronger on the latter. Analysis is becoming more nuanced. Not all food production, for example, should be counted as a contributor towards the goal of Zero Hunger. The negative environmental effects of electrification, such as cobalt sourcing for batteries, should be considered as well as the carbon-cutting advantages.

In gaining a more robust picture, it can be helpful to use multiple data sources for the same metrics. For example, we note that on the subject of greenhouse gases, some providers are doing better at obtaining Scope 3 data (e.g. emissions by first-tier suppliers), while others have made better progress on including the wider range of gases that can cause global warming: both of these factors can make a meaningful difference to scores.

When looking at the data that asset managers are providing to investors, we do still see US managers lagging far behind their European counterparts when it comes to both ESG reporting and impact reporting. The picture does vary, however, depending on how important it is for US managers to attract European clients: in US asset classes where domestic fundraising has been straightforward (e.g. private equity), managers’ attitudes are less likely to have changed.

Carbon: the topic du jour

Carbon reporting, undoubtedly the most advanced of the impact sub-themes, is also an area where the gap between Nordic and Dutch investors and the rest of the globe is somewhat narrower: 64% of investors in this region are assessing the carbon emissions associated with their portfolio versus 46% of global investors, and – when we add on the percentage who are “actively considering” doing so – the difference looks set to shrink even further. National and supranational regulations, the development of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the evolution of PRI reporting (which now includes TCFD disclosures) and other developments have helped to drive a broader global cohort of investors forward.

The possibility of measuring carbon emissions opens the door to the introduction of two types of targets: targets around reducing emissions, including the increasingly widespread adoption of ‘Net Zero’ goals (usually by 2050), and targets for building up the framework for measuring emissions (such as assessing emissions associated with a certain percentage of the portfolio or certain asset classes by a certain date). In some cases, investors are beginning with an ultimate objective and working backwards to the implementation subject; in other cases the investors are beginning with assessing current emissions and the feasibility of reducing them before putting reduction targets in place. “Last year we introduced a net-neutrality target for carbon emissions,” explains Arkko, “with a path where we set five-year targets, and then after five years, we’ll put in new targets depending on where we are at that point. The starting point is to build roadmaps for each asset class, which is what we’re working on now.”

Pieter van der Ende,

Pieter van der Ende,Investment Manager, Rabobank Pensioenfonds

We established a target to reduce the emissions in the equity portfolio by 50% by the end of 2022… Looking ahead we want to measure emissions in other asset classes as well and see what sort of reduction targets would be feasible for those asset classes and perhaps for the overall portfolio.

As with the broader impact issues discussed above, it is common to for investors to begin their implementation journey in equities due to data availability. Private investments are proving particularly difficult; current approaches tend to rely quite heavily on industry averages rather than the precise assets involved. There are interesting initiatives underway to improve carbon footprint measurement in private assets, such as the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) in the Netherlands.

When seeking to reduce the carbon emissions associated with their portfolios, investors are extremely aware of the need to avoid an overly simplistic approach. “It would be very easy to do this by getting rid of certain sectors and having a lot of investments in forestry, but we understand that the world needs certain industries and we want to be part of the transition,” a Nordic investor explained. The goal is to encourage change rather than to decarbonise. This approach also includes focusing on the actions that investee companies are taking to reduce their own emissions. “We select to be invested in companies whose carbon footprint is going to improve in the next three-to-five years,” says Gijsbers. In Sweden, Lööw is paying close attention to science-based targets for carbon emissions used by portfolio companies: “They’re a leading indicator of where things are heading,” he explains, “whereas carbon footprint has limited use with regards to the direction of travel.”

Although impact-minded investors are glad to see carbon reporting becoming mainstream, many of the Nordic and Dutch investors we spoke to are keen to point out that “only looking at the green side [of ESG] is not enough,” and subjects beyond carbon deserve close attention within the ‘E’ agenda; in this respect, the EU’s current focus on biodiversity is very welcome.

More impetus for impact investing

Impact investing, depending on how one defines it, has predated the professionalisation of impact measurement. Renewable energy infrastructure, green bonds, social housing, microfinance and other investments gained traction even before overall portfolio impact was conceived in measurable terms. However, it is a truism that what gets measured gets managed: the improving visibility and clarity on various impact metrics should galvanise and inform efforts to drive positive change through investment.

Investors broaching this area face two distinct challenges: First, how do we define impact investing? While the language provided by the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) can be a helpful starting point, the subject looks very different across different asset classes, so investors can find it helpful to create sector-specific definitions. In some cases we see practitioners considering two tiers of impact investment, such as in situations where certain green bonds might not meet the threshold for the higher tier.

Jos Gijsbers,

Jos Gijsbers,Senior Portfolio Manager, ASR Nederland N.V. (Asset Management)

We established a target in 2018 to invest at least EUR 1.2 billion in impact investments by the end of 2021. We already hit that target, with the majority invested in green bonds that meet our impact classification criteria. Following the general GIIN definition we developed a more specific definition for each asset class – how we define an impact investment in sovereign bonds, how we define it in real estate and so on. With those more specific definitions we involved all investment teams to contribute to this impact target and measure what qualifies as an impact investment.

The second challenge is perhaps even more critical, especially when regulations determine the investor’s obligations: how do you align these strategies, very clearly, with the necessity of ensuring that financial returns are not compromised? “There is now a better understanding that you do not necessarily need to give up financial returns,” says Arkko, who has faced this question with Ilmarinen. “This is a question we’ll be focusing on and researching in the coming year.”

Carving out specific allocations to impact strategies represents a controversial topic with investors taking different approaches. On the positive side, dedicated targets can be helpful in ensuring that resources, research and institutional attention are directed towards areas that might otherwise have been overlooked due to unfamiliarity rather than unattractiveness. Yet one can argue that these issues could be addressed without creating a specific percentage allocation. “We don’t have an allocation to impact investments, and I don’t think that’s an approach we’re likely to take,” says van der Ende, who integrates strategies such as renewables into the main portfolio. “We’ve been approached about various strategies that have an impact agenda and clear SDG goals, such as agriculture private debt, but these don’t necessarily fit our process,” he adds, acknowledging the difficulties that can be involved when an integrated approach is used. “We want to set out a new approach in this area so that we can do more, and be clearer about what it is we expect, without having a separate impact portfolio.”

The hunt for impact investments has, in some cases, led investors towards new geographies and strategy types that have proved beneficial for overall portfolio diversification. “Impact investing took us into geographies and markets that we did not invest in before,” says Lööw. “We now have a private debt investment in emerging markets… We didn’t have any investments in private debt or emerging markets before this.”

Looking ahead: a work in progress

No impact-oriented investor, irrespective of location or size, is satisfied with its current approach or the tools and information available. Exploration and innovation will continue. First movers are carving a path for others to follow – seeding new strategies, acting as the foundational clients for new service providers and shaping the frameworks that others will subsequently adopt.

The probability that others will follow appears, at this point, to be a certainty. The data shown here illustrates investors’ clear progress toward the adoption of impact-oriented approaches. More fundamentally, the shift in favour of thinking about ‘outcomes’ is integral to the professionalisation and long-term credibility of the broader ESG agenda. The ability to measure outcomes creates transparency around ESG matters, improves accountability and enables top-down management across any portfolio. Impact investing is, undoubtedly, here to stay.

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

English (Global)

English (Global)  Deutsch (DACH)

Deutsch (DACH)  Italiano (Italia)

Italiano (Italia)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  English (Canada)

English (Canada)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)