bfinance insight from:

Kathryn Saklatvala

Head of Investment Content

Sam Greene

Associate, Private Markets

Private debt investors are eyeing apparently superior returns in healthcare lending, with funds’ net IRR targets suggesting a premium of more than 300bps versus conventional direct lending strategies. New dedicated healthcare lending funds are also emerging, with larger private debt managers joining a fray that was historically dominated by smaller specialists. Yet some of the sector’s defining characteristics—cashflow-light companies, a high proportion of ‘unsponsored’ transactions and creative deal structures—can be difficult pills for even an experienced private debt allocator to swallow.

It is undeniable that the private credit asset class has shown remarkable strength amid the macroeconomic shifts of the 2020s. Asset manager fundraising has also remained relatively strong (barring a dip in Q1 2024) even now that rates have entered a phase of gradual decline. Yet investors must keep a watchful eye on portfolios amid shifting supply-demand dynamics, a modest rise in defaults and growing reliance on Payment in Kind (PIK). Investors can make adjustments to improve resilience and risk-adjusted returns in private credit allocations. This includes considering the role of satellite exposures to less well-trodden sub-sectors of lending and finance.

Jargon Buster: PIK

Payment in Kind (PIK) enables a borrower to make interest payments in a form other than cash, such as equity or additional debt (a larger principal), during the term of the loan. With higher interest rates, use of PIK (and so-called ‘Synthetic PIK’) is increasingly prominent. This shift affects both the yield and risk profile of private debt strategies.

One area enjoying such attention at present is healthcare lending: a niche but long-established strategy, historically occupied by a modest list of relatively small funds and popular with family offices. Today, this sector is becoming larger and more institutionally oriented. We now estimate that there are more than twenty-five dedicated healthcare lending strategies (encompassing direct lending and royalties), nearly half of which are focused solely on direct lending. The list is dominated by long-running specialist boutiques such as CRG and Pharmakon Advisors, but it has been strengthened by recent first-time fund launches from private credit houses with a history of deals in the sector (Ares, Oaktree, et cetera).

A healthcare premium?

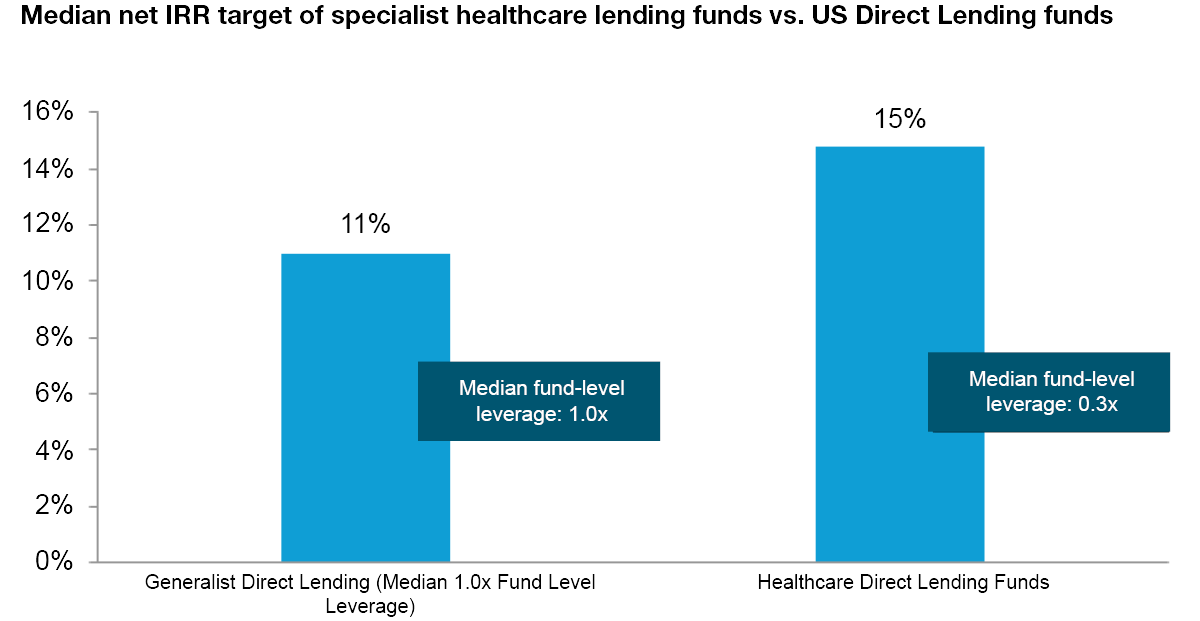

The latest manager research data from bfinance shows healthcare lending funds offering a substantial return premium: the median net IRR target for healthcare direct lending strategies, according to new data, is nearly 15%, versus 11% for generalist US direct lending strategies (see chart below). Importantly, these higher returns cannot be attributed to fund-level leverage: the healthcare strategies in this sample had median fund-level leverage of 0.3x, versus 1x for the generalist funds.

Source: bfinance, manager research 2023-2024. Stated net IRR targets do not accurately predict future performance. There is substantial variation between managers, with IRR targets significantly higher and lower than the median figures provided here.

These asset managers lend to companies whose scope extends far beyond traditional patient care provision, including ‘life sciences’ firms (pharma and biotech, suppliers of medical technologies, tools and diagnostics), healthcare IT companies and ‘specialty’ service providers such as medical transport services or group purchasing organisations. Yet what, fundamentally, drives higher returns? Companies in this universe are often poorly served by the banking sector. They are also overlooked by mainstream direct lenders due to distinctive characteristics that are explored further below. And, while some firms can generate cash via pharmaceutical and biotech royalties, this is not an option for all. Even for those who can pursue this route, the investment appeal of royalties has been somewhat dampened when compared with credit (bonds or private debt) in a climate of higher interest rates. Specialist lenders—featuring expertise from the related spheres of healthcare venture and healthcare banking—can inject themselves into a financing gap.

Five sector-specific symptoms

- Low cashflows are commonplace

- Fewer private equity sponsors; more ‘listed’ companies

- Unusual deal structures

- ESG risks need attention

- Higher fees

Classic direct lending is built on businesses with high cashflows: it is cashflow that underpins the promise of repayment. Healthcare, however, bucks the pattern. With businesses typically making hefty investment into research and development as well as commercialisation (sales and marketing) to support growth, it is common to see cashflows in low or even negative territory – even while lenders talk confidently about the “path to profitability.”

An expert lender, however, can still underwrite businesses with these characteristics. Low cashflow doesn’t mean low top-line revenues or a low cash balance. Investors can focus on the liquidity covenants that accompany transactions and how they’re worded. Guard rails can be put in place. In theory, spending on R&D can be curtailed if need be; excess dollars spent on commercialisation can be reduced; payments to other parties (such as dividends to owners), can be restricted; assets can be sold. Lenders can make substantial use of PIK, often to a greater extent than conventional direct lenders. Above all, it is important that the lender enters these transactions with a conservative view on prospective growth: companies often fall short of their own lofty expectations and a responsible lender will not engage in over-optimism that subsequently necessitates growth-strangling measures.

Mainstream direct lending is dominated by sponsor-backed transactions (lending to firms that have a private equity investor). bfinance manager research data indicates that nearly 90% of deals in the average US direct lending fund are sponsored transactions. In healthcare lending, however, the picture is very different indeed: here, unsponsored deals can represent 40-70% of an overall fund portfolio. Moreover, the bulk of that unsponsored group are publicly traded companies.

Without a private equity firm involved, unsponsored transactions often require a closer and more resource-intensive relationship between lender and the company’s management.

This difference has several implications. Specialist expertise becomes even more significant: without a private equity firm involved, unsponsored transactions often require a closer and more resource-intensive relationship between lender and the company’s management. Due diligence is more onerous: it can be challenging to obtain appropriate information from a publicly traded healthcare company that will typically be very concerned about confidentiality. Various credit safeguards become even more important: after all, equity is generally the first line of defence against a potential default event and this is less straightforward in a sponsor-less transaction. Leverage (LTV) is typically lower when lending to a listed company.

Healthcare lending is rife with esoteric deal structures. This is a marked contrast versus generalist direct lending strategies, where asset managers broadly use a similar structure for most of their deals. Here, the way that each loan is structured and the measures put in place to safeguard it tend to be highly specific to the borrower with a variety of moving parts including warrants, patents and more. For investors, this difference makes manager selection and due diligence somewhat more challenging and technical.

Another key distinction of deals in this space is shorter average duration: it is typical for loans to be refinanced within one-to-two years, versus two-to-three years in traditional direct lending. The overall lifespan of a pooled fund in this area, however, is similar. As such, funds will have higher portfolio churn with a need to reinvest capital more frequently.

The healthcare sector presents distinct ESG risks, particularly from a social perspective. Many underlying users fall within the 'vulnerable' category, and the risks associated with healthcare provision can be highly sensitive. Issues such as drug pricing, access to care and the handling of drug testing create complexities that are unique to this industry. For instance, disparities in healthcare pricing between the EU and the rest of the world raise important questions. Price gouging in the pharmaceutical industry, while problematic across the board, is especially concerning in regions that lack universal or heavily subsidised healthcare systems. There are notable risks associated with drug approval processes, where clinical trial procedures need to be fully understood.

Moreover, healthcare is characterised by a constantly evolving regulatory environment, with the potential for product recalls adding further uncertainty. Drug recalls can pose significant risks, particularly when royalty streams are dependent on drug sales. This reinforces the importance of experienced managers, particularly those with backgrounds in medical professions or healthcare banking, to navigate these challenges effectively. These managers should also engage third-party advisors when necessary, particularly in the field of pharmaceuticals, where drug safety and efficacy concerns can have long-term, unforeseen consequences—consider, for example, the opioid crisis.

Investors also need to be aware of the ESG complexities that can arise in the event that a covenant is breached or, worse still, a default occurs. When a firm is providing a clear social benefit, taking steps that affect the firm’s operations (even if necessary from a financial point of view) may create social damage. Even investors who are not deeply engaged with ESG concerns must be mindful of the reputational risks associated with undermining healthcare provision, particularly when highly vulnerable populations are affected.

Given the sector’s esoteric deal structures, higher portfolio churn and other complexities outlined above, it should not come as a surprise that healthcare lending managers charge significantly higher fees than their generalist direct lending counterparts. Yet investors may be surprised at the degree of difference involved.

Based on fund manager research in 2024, the median management fee for healthcare lending strategies is currently 1.45% (versus 1.0% for generalist US direct lending funds). Performance fees vary from around 10% to 20% but are predominantly clustered at the higher end of that range, while the median performance fee for generalist US direct lending funds is currently 12.5%. Meanwhile, despite a difference of more than 300bps in average net IRR targets, the two groups use similar hurdle rates.

Investors focused on net-of-fee returns and seeking the best value for money should not be deterred by the cost: after all, the substantial premium anticipated above takes fees into account. Yet it is important to be aware of this issue, set stakeholders’ expectations appropriately, consider alignment of interest and keep a watchful eye on fund terms.

A prescription for profit?

For investors who are considering how to improve the overall performance, diversification and ‘all-weather’ resilience of private debt portfolios, the burgeoning healthcare lending sub-sector represents an interesting candidate for a satellite allocation. Yet the very sector characteristics that produce attractive returns can create difficulties for private debt allocators. Robust manager research and due diligence that reflect the complexities of the asset class are key ingredients for success.

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

Français (France)

Français (France)  Deutsch (DACH)

Deutsch (DACH)  Italiano (Italia)

Italiano (Italia)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  English (Canada)

English (Canada)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)