bfinance insight from:

Sarita Gosrani

Director of ESG and Responsible Investment

Kathryn Saklatvala

Senior Director, Head of Investment Content

Frans Verhaar, CFA

Senior Director

When selecting and monitoring external investment managers, it is increasingly important to develop a clear understanding of their credibility in ESG, sustainable and impact investment matters. The subject is a challenging one, with asset managers’ practices (and appearances) evolving rapidly.

This article was originally published in VBA Journaal, the professional journal of the CFA Society of the Netherlands. To view the article in its original form, visit the CFA Society website.

Institutional investors are coming under growing pressure to get this right. Regulators are evidently willing to show teeth on the greenwashing subject, with a few asset managers already facing financial penalties – such as Goldman Sachs Asset Management, which incurred a $4 million fine in a recent particularly high-profile ruling by the US Securities and Exchange Commission . Such cases can also inflict reputational damage on asset managers’ clients. Meanwhile, attempts by regulators and policymakers to provide clarity via categorisation and oversight, while in many ways positive, have generated controversy and confusion. This double-edged effect is illustrated by the evolution of the European SFDR (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation) framework and asset managers’ widespread reclassifications of funds, such as downgrades from SFDR Article 9 to 8 or from Article 8 to 6.

Looking beyond such pressures and regulatory interventions, we also believe that ESG analysis and sustainable investment practices are fundamental to sound investment decision-making. Many pension schemes, endowments, insurers and other investors have—independent of regulatory expectations—made clear, high-level commitments on ESG integration and related subjects such as decarbonisation and impact. Those commitments must now be delivered for stakeholders, with the support of investors’ asset manager partners.

To assess and monitor investment managers effectively, investors must evaluate ESG practices at both product/strategy level and firm level. In this article, we highlight four key challenges that investors face today during ESG analysis. While there are many facets to ESG and impact due diligence, a focus on these four issues can help investors to gain clarity on the credibility of their prospective and current partners.

- Challenge 1: Assessing managers’ commitment to sustainability amid great marketing.

- Challenge 2: Identifying stronger versus weaker approaches to climate change.

- Challenge 3: Ensuring ESG integration through the full investment lifecycle.

- Challenge 4: Cutting through ‘impact washing’.

The article presents some quantitative data on managers’ practices in these areas, gathered through recent surveys and research. Yet, as the discussion below reveals, it is crucial to look beyond superficial indicators, which can often be misleading: the devil is in the detail and sound ESG integration processes can rarely be identified via box-ticking or fund labels. Assessments should also be sensitive to the specific asset class and those analysing managers should have a strong up-to-date awareness of current ESG practices within that asset class. Finally, due diligence should straddle both ‘investment’ and ‘operational’ aspects, even though investors typically handle these two subjects separately. This can be difficult, since personnel on each side do not tend to have the full picture, are likely to have different priorities and may lack specific expertise on ESG/impact subjects.

Challenge 1: Assessing managers’ commitment to sustainability amid great marketing

It’s been nearly twenty years since management consultant Peter Drucker coined the phrase: ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’. When considering asset managers’ ESG credibility, one of the most important and desirable characteristics is also one of the hardest to assess: robust sustainable investment commitments and beliefs running through the organisation, from senior leadership downwards.

Identifying genuine commitment has become far more difficult now that ESG has become a commercial imperative for asset managers. Firms are keen to convey an ESG-aware image to their investors and stakeholders and, in our day-to-day experience, risk losing assets if they do not. While we should not take away from the strides that investment managers have made on this subject, the presence of strong commercial motivations does naturally encourage a degree of greenwashing.

It is not always easy to look beyond the polished marketing materials, mission statements, sustainability reports and well-versed salespeople. It can help to examine three subjects more closely: firm-level commitments, accountability and ESG staffing. In all cases, the analysis must be nuanced: it is not enough to understand whether managers have policies and an ESG headcount; overly simplistic scorecards should be avoided. Examinations should also be sensitive to variables such as the size of firm and the asset classes covered.

Policy substance can demonstrate firm-level commitment to sustainability

While the vast majority of firms do now have an ESG or responsible investment policy (or policies), they are not all equally detailed in terms of substance. It remains common, for example, for policies to lack asset class-specific guidelines, which can be helpful in ensuring alignment and consistency while also highlighting areas of necessary difference. Moreover, there is also clear differentiation between firms in terms of the degree of internal accountability for those policies.

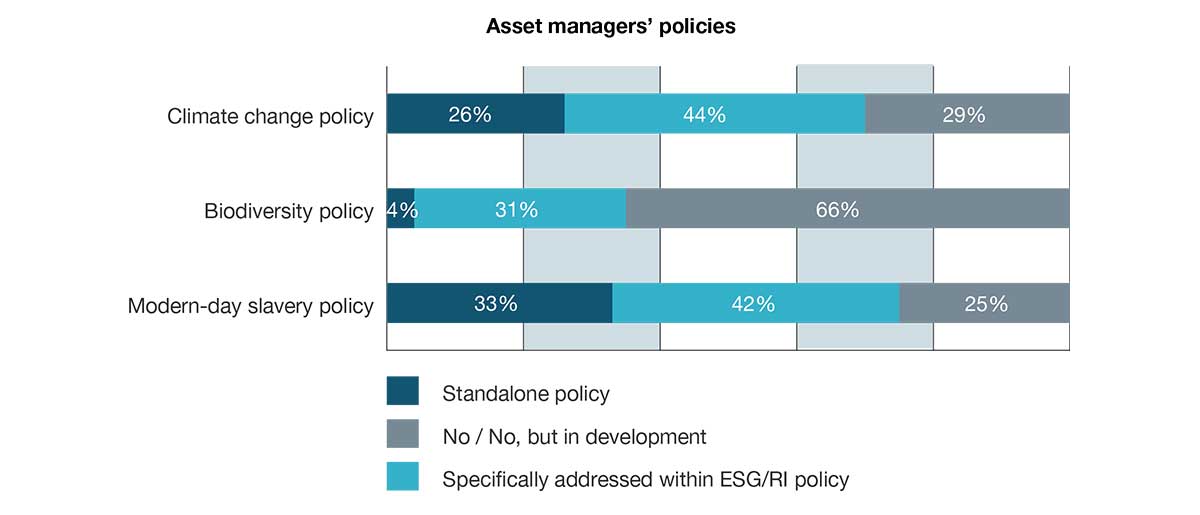

Our research indicates that 70% of asset managers address climate change at policy level—either within the ESG/RI policy or in a standalone policy—while just 34% of managers address biodiversity at policy level (and only 4% have a standalone policy on this subject). From a social perspective, notably, 25% of managers do not address Modern Day Slavery at policy level. Where the manager addresses a topic within their ESG/RI policy, this can indicate a high-level reference rather than in-depth coverage.

Source: bfinance, ESG asset manager survey (72), 2023

When thinking about policies, it is also worth looking at companies’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes, in part to understand whether a manager ‘walks the walk’ as a company, as well as ‘talking the talk’. According to our latest data, only 57% of managers have firm wide CSR policies. While 80% have a policy on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI), many are not able to provide specific data points relating to this subject in their firm—although we believe that this is now improving quite rapidly.

Firm-level pledges or objectives can also take the form of participation in external bodies and initiatives. ESG and sustainability are subjects that inherently need industry collaboration if meaningful progress is to be made. Many asset managers can provide long lists of initiatives to which they subscribe, but the bar for involvement can be low. Indeed, Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) has received criticism over the years for its failure to impose requirements beyond signatories’ financial contributions; they began to delist signatories for the first time in 2020 but there have been very few cases thus far . Investors can go further and ask for tangible examples of asset managers’ contributions within those initiatives.

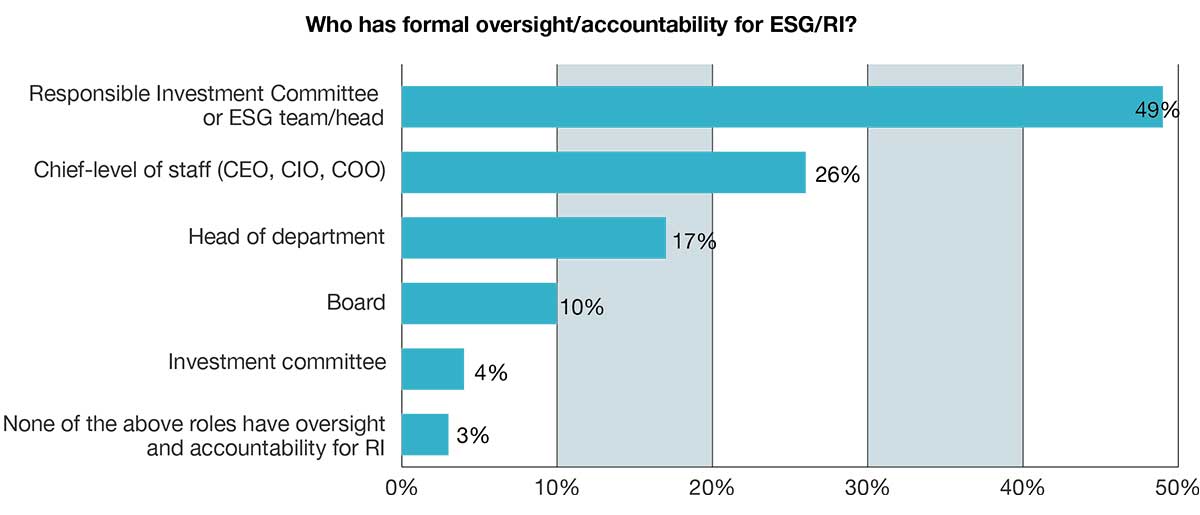

Accountability and oversight processes reveal ESG governance

As well as the substance of ESG policies, investors can look at the nature of accountability and oversight. This subject can easily be overlooked but has a key role to play in the asset manager’s own ability to mitigate greenwashing internally. It also helps to show the importance that is placed on the topic by the senior leadership of the firm. Ensuring strong accountability and audit of the ESG approach is not only important in ‘investment due diligence’ but is also increasingly relevant in ‘operational due diligence’, given the potential consequences of inadequate controls in today’s market.

Managers can take a vague approach to accountability. More than one in eight say that formal accountability for ESG/RI oversight lies with a department head; nearly half say that the Responsible Investment Committee is formally accountable for ESG/RI matters. Only one in four place responsibility with the senior leadership (C-level). We typically prefer to see policies approved by the Board and accountability lying with senior leadership alongside a dedicated ESG individual. Going a step further, we would argue that best practice entails running risk management, compliance and internal audit processes at product level to assess how an investment team has applied the firm’s policy to ESG within a specific fund: this practice is growing among asset managers today.

Source: bfinance, ESG asset manager survey (72), 2023

ESG resourcing is not a clear-cut issue

As an asset management firm develops a stronger focus on ESG, this will typically be accompanied by a rising headcount dedicated to this subject as well as the purchase of data (discussed in a subsequent section) and the provision of other relevant resources.

On the staffing side, our recent research indicates that 90% of asset managers have dedicated ESG personnel. Team size varies greatly, with some managers having just one dedicated individual and others more than 30. The structure of the ESG teams also varies: centralised functions, dedicated specialists within asset classes or a combination of both are all common. This is supplemented in some cases with external expertise, be it consultancy/advisory or academic. Scientific involvement can be particularly helpful in certain subjects, such as climate change and biodiversity, given the complexities surrounding these topics.

There is no right or wrong answer when it comes to the size or structure of an ESG team, though larger managers without obvious resource constraints are expected to demonstrate a strong headcount. As ever, the devil is in the detail. While ESG headcount can be a useful indicator of genuine firm-level commitment, ESG teams and specialists can often be siloed and may lack clout with underlying investment teams. It is therefore very important to understand the roles and responsibilities of ESG individuals and their interactions with the investment team: do they offer support and guidance or conduct the full ESG analysis? The rapidly evolving nature of ESG issues calls for dedicated expertise. Yet we consider genuine ESG integration to be visible where there is no longer a stark separation between ESG and financial analysis and when sector analysts and portfolio managers can all enthusiastically describe ESG risks and opportunities inherent in their investments without the ESG team’s presence.

Challenge 2: Identifying stronger versus weaker approaches to climate change

The risks posed to society and the economy by climate change are now well articulated and quantified. There is no lack of information and data to support the view that climate risk considerations are financially material and should therefore be incorporated into the investment process.

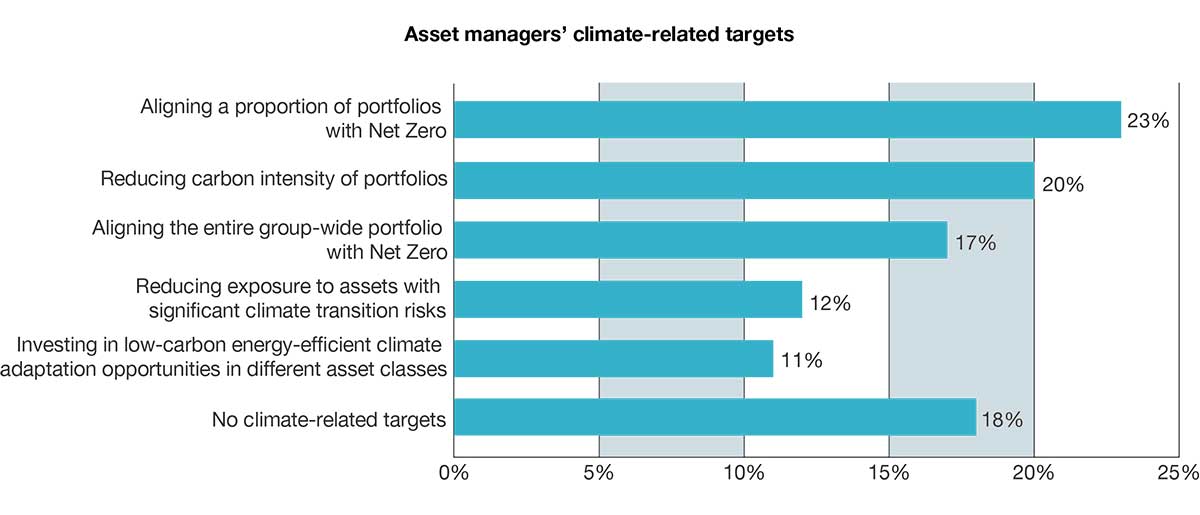

Regulatory requirements, investor demands, and even potential reputational risks have led investment managers to take a stance on climate change, including establishing climate-related targets. We now estimate that nearly a quarter of asset managers are aligning at least a proportion of their portfolios with ‘Net Zero’ goals, and fewer than one in five have no climate-related targets at all. Interestingly, the PRI estimates that only 14% of signatories link climate-related KPIs to management team remuneration and just 10% link them to executive remuneration.

Source: bfinance, ESG asset manager survey (72), 2023

At firm level, targets and commitments are often connected to managers’ involvement with programmes such as the Net Zero Asset Manager Initiative, the Taskforce for Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and Climate Action 100+, to name a few. Participation in these initiatives can be key to kick-starting change internally, while industry collaboration also helps to drive forward the climate agenda. The Net Zero Asset Manager Initiative (NZAMI) has currently 301 signatories representing around €55 trillion in AUM. However, there is still a long way to go: only 43% of PRI signatories, for example, publicly support TCFD recommendations.

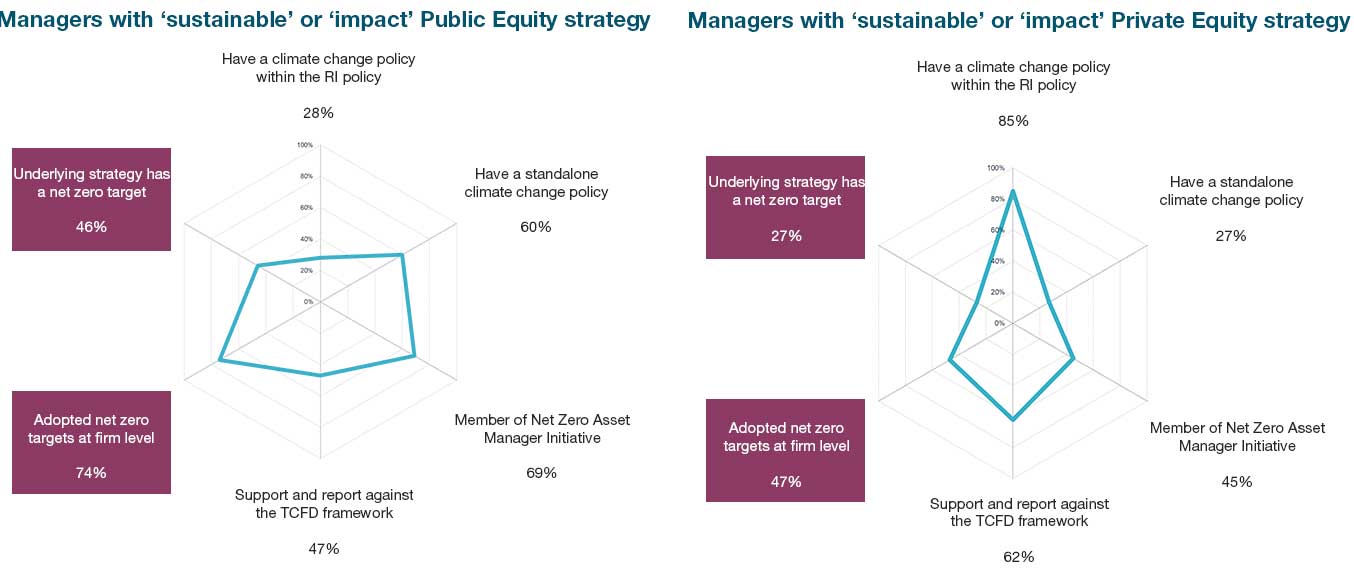

It is important to observe that firm-level Net Zero targets and involvement in initiatives such as NZAMI do not necessarily translate to commitments for the manager’s underlying funds. Interestingly, as shown below, this is true even where the underlying fund has a specific ‘impact’ or ‘sustainable’ remit (and, as such, might reasonably be expected to be more likely to embody the manager’s ‘Net Zero’ objective than other products in their roster). Moreover, this significant difference between firm-level Net Zero commitments and strategy-level Net Zero objectives (even for sustainable/impact strategies) persists across both liquid and illiquid strategies, so it cannot simply be attributed to the often-discussed data availability challenges in private markets. For example, 74% of managers with ‘sustainable’ or ‘impact’ strategies in Public Equity have firm-level Net Zero targets, but only 46% have a Net Zero target for the strategy in question (a ratio of about 1.6:1). On the Private Equity side the figures are lower (47% and 27% respectively), with a similar ratio of 1.7:1.

Climate-related commitments from asset managers with ‘sustainable’ or ‘impact’ strategies in different asset classes

Source: bfinance, 2023. Data covers 103 managers with a ‘sustainable’ or ‘impact’ public equity strategy and 55 managers with a ‘sustainable’ or ‘impact’ private equity investment strategy (self-selecting). Where a manager has both strategy types they are included on both sides.

Moreover, even where fund-level Net Zero targets are in place, the existence of these objectives is not necessarily commensurate with managing climate risks within the investment process; managers’ approaches to implementing those net zero targets vary greatly in terms of sophistication. Climate-related targets, the strategy for delivering those targets and the degree of success in achieving those targets should be considered through both ‘investment due diligence’ and ‘operational due diligence’ lenses: different questions will be prioritised on each side. Investors must also consider the extent to which they will be satisfied the achievement of those targets superficially in their portfolio versus the delivery of ‘real-world change’ through reducing the carbon footprint of investee companies (ideally with holistic assessments of investee companies’ exposure to climate risks) or supporting the development of less environmentally damaging technologies and processes.

Many asset managers in public and private market asset classes have now developed methodologies to explicitly incorporate climate change within the investment and risk management processes. Data from the PRI indicates that 50% of signatories incorporate climate-related risks when considering traditional investment risks (e.g. credit, market, liquidity, operational). Meanwhile, 35% say that their risk committee is formally responsible for identifying, assessing and managing these risks. Our own analysis indicates that only 55% of managers provide climate-related data to investment professionals on the same platform that is used for traditional financial data and analysis. Active ownership programmes also increasingly show a strong focus on driving positive outcomes relating to climate change among investee companies, but our recent research indicates that only around half of asset manager stewardship policies specifically mention climate risks and opportunities.

One interesting area of current development, in our view, is the way in which a manager approaches the financials of decarbonisation in an investee company. The more common route is to assess whether the company has set a net zero target, whether it is ambitious and whether it is in line with the Science Based Target Initiative. Yet targets can be superficial or even problematic if the financials do not stack up. As such, we do now see approaches that involve pricing in and/or assessing the viability of the CAPEX and OPEX required to truly decarbonise the company, and pushing for that to include ‘Scope 3’ emissions where possible. This approach, however, is still not widespread.

Challenge 3: Ensuring ESG integration through the full investment lifecycle

There are many stages to the lifecycle of an investment, from determining the potential investment universe through to investment selection and due diligence, followed by managing the asset—which may include active ownership, monitoring and reporting—and ultimately concluding an exit/sale. Whatever the asset class, it is important for asset managers to have a thorough, cohesive approach from the start to end of the investment lifecycle rather than focusing heavily on two or three areas and overlooking others. Furthermore, ‘best practice’ at each stage should look different depending on the asset class, sub-sector (e.g. geography) and investment style (e.g. holding periods): ambiguous process descriptions that are not asset class specific should be viewed with caution.

At pre-investment stage, it is important to understand how the asset manager has defined the investment universe, including (positive or negative) screens and data sources used for the screening process. While this part of the process can be more challenging in private markets, there are number of third-party providers that can be used to support assessment and subsequent monitoring.

Once the investment universe has been defined, managers should be able to demonstrate a robust, repeatable process to incorporate ESG considerations into due diligence. Characteristics of strong practice include developing ESG data using proprietary analysis, combining this with third-party data sources, forming views on the material risks and opportunities affecting an investment and reflecting these in the investment thesis or investment committee memos which are used in the decision-making process. Leading managers even go a step further and demonstrate the weight placed on ESG within decision making and may even make valuation adjustments to ‘price in’ ESG, whether that takes the form of integration into financial assumptions, covenants or costed corrective actions (such as in the 100-day post-investment plan for private market assets).

In practice, however, we find during our day-to-day investment consultancy activities that asset managers’ practices deviate considerably from this ideal. We do still see some asset managers placing excessive reliance on third-party data providers: external data does have a pivotal role to play in ESG programmes but investors should be particularly wary of managers depending heavily on a single provider and taking their data at face value without further interpretation. We also see some firms giving portfolio managers a large amount of discretion on whether to incorporate ESG analysis into their decision-making: investment managers with personal biases on the topics and/or a lack of willingness to adapt their existing decision making may take a superficial tick-the-box approach or, worse, ignore the topic all together. We’ve also experienced firms offering artificial polished examples of due diligence memos, rather than real-life redacted samples in which ESG features prominently. Some managers only reveal red flags during live due diligence discussions, such as a tendency for investment seniors to deflect ESG-related questions to the ESG person in the room.

Following the investment, asset managers should demonstrate strong active ownership processes. Stewardship is fundamental to managing ESG risks and achieving real world change relating to sustainability; investors can look for a high degree of transparency, robust practices in voting and engagement, use of milestones, evidence of tangible positive outcomes and escalation processes. Monitoring/reporting and clear inclusion of ESG issues within risk management are also key in the post-investment stage. We see many examples of weak practice here. By way of an illustrative example, we recently assessed a private markets manager who relied on periodic manual internet searches to reveal real-time news about controversies affecting their holdings.

ESG considerations are also highly relevant when exiting an investment. Where the asset can be traded, managers take different views on the role of divestment as part of a credible ESG-oriented strategy. For closed-end private market strategies that require exits in order to realise value for Limited Partners in the fund, it is useful to consider how the manager has sought exits that promote sustainability rather than undermine it.

Challenge 4: Cutting through ‘impact washing’

Investors can now access a rapidly expanding range of ‘impact’ strategies across various asset classes, some of which adopted the EU SFDR ‘Article 9’ label though others chose not to take this path. These target the dual objective of generating measurable positive environmental and social outcomes alongside financial returns (although some highly impact-focused investors may place less focus on the latter).

Not all impact products are created equal, however, and this sector is particularly difficult to navigate given its immaturity. Due diligence of impact products must assess not only of the credibility of the impact process—with intentionality, additionality and measurability in mind—but also the manager’s ability to balance impact outcomes and financial returns. The sector is rife with ‘impact washing’, wherein strategies can be dressed up to look significantly more impactful than is justified by a more thorough analysis of their processes.

Impact washing often takes the form of ‘SDG washing’, whereby managers seek to associate investments with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. While SDG alignment can be interesting and helpful when done well, there is no standardised approach. In practice, managers have been very creative in aligning companies to SDGs: one recent manager assessment, for example, saw a luxury chocolate retailer being mapped to the ‘Zero Hunger’ goal. Assessment is primarily based on ‘percentage of revenue’ alignment to an SDG, but the thresholds used by managers vary, with figures as low as 50% of revenues. Furthermore, alignment with the high-level SDGs can be extremely superficial versus a more granular approach that looks at the 169 underlying targets and, even then, further probing can be required on subjects such as the geographies targeted (e.g. emerging versus developed markets).

There is huge differentiation between managers in terms of their approaches to impact investing and the picture is evolving rapidly. Best practice involves focusing on a company’s philosophy to deliver positive outcomes, quantifying target KPIs for impact in line with financial analysis and considering the ESG risks and potential negative impact of the company. Investment managers leading the charge in this space tend to incorporate industry initiatives such as the ‘five dimensions of impact’ from the Impact Management Project (IMP), and have created methodologies to consider the impact per dollar invested.

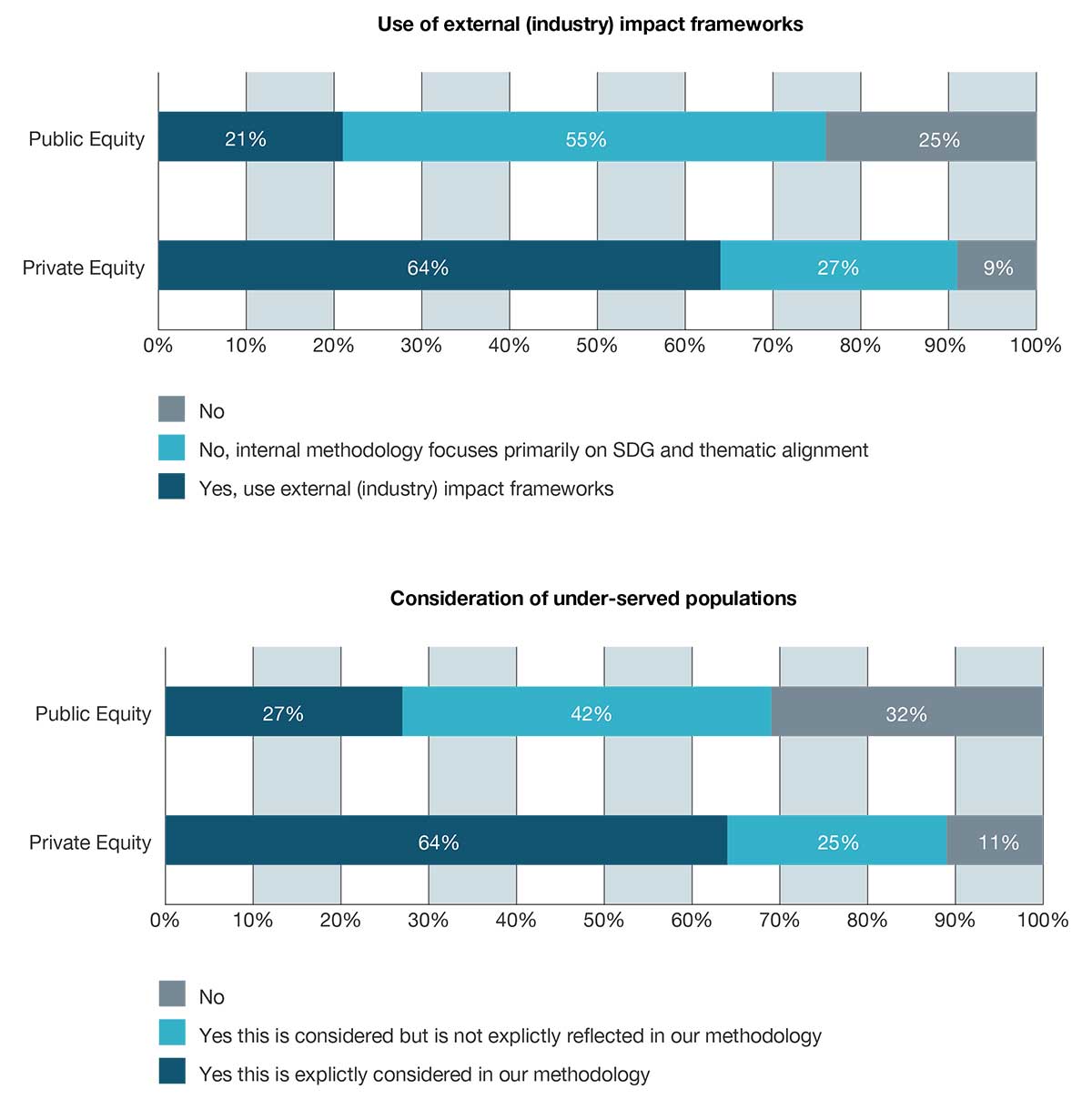

Here, again, we see significant differences between managers based on the asset class in which they operate. If we revisit the universe of explicit ‘sustainable’ and ‘impact’ strategies that was examined in ‘Challenge 2’, we find some interesting distinctions at play; a couple of these are illustrated in the charts shown here.

Source: bfinance, 2023. Data covers 103 managers with a ‘sustainable’ or ‘impact’ public equity strategy and 55 managers with a ‘sustainable’ or ‘impact’ private equity investment strategy (self-selecting). Where a manager has both strategy types they are included on both sides.

As always, investors should be very cautious when relying on managers’ assertions in response to impact-related questions. Closer examination of managers’ philosophy and methodology is not always supportive of their assertions. For example, while well over half of managers with sustainable/impact strategies claim to consider under-served populations within their methodology (either explicitly or implicitly), this is less strongly evidenced in practice than we would wish.

‘Impact economy’ and ‘double materiality’ concepts are becoming more mainstream

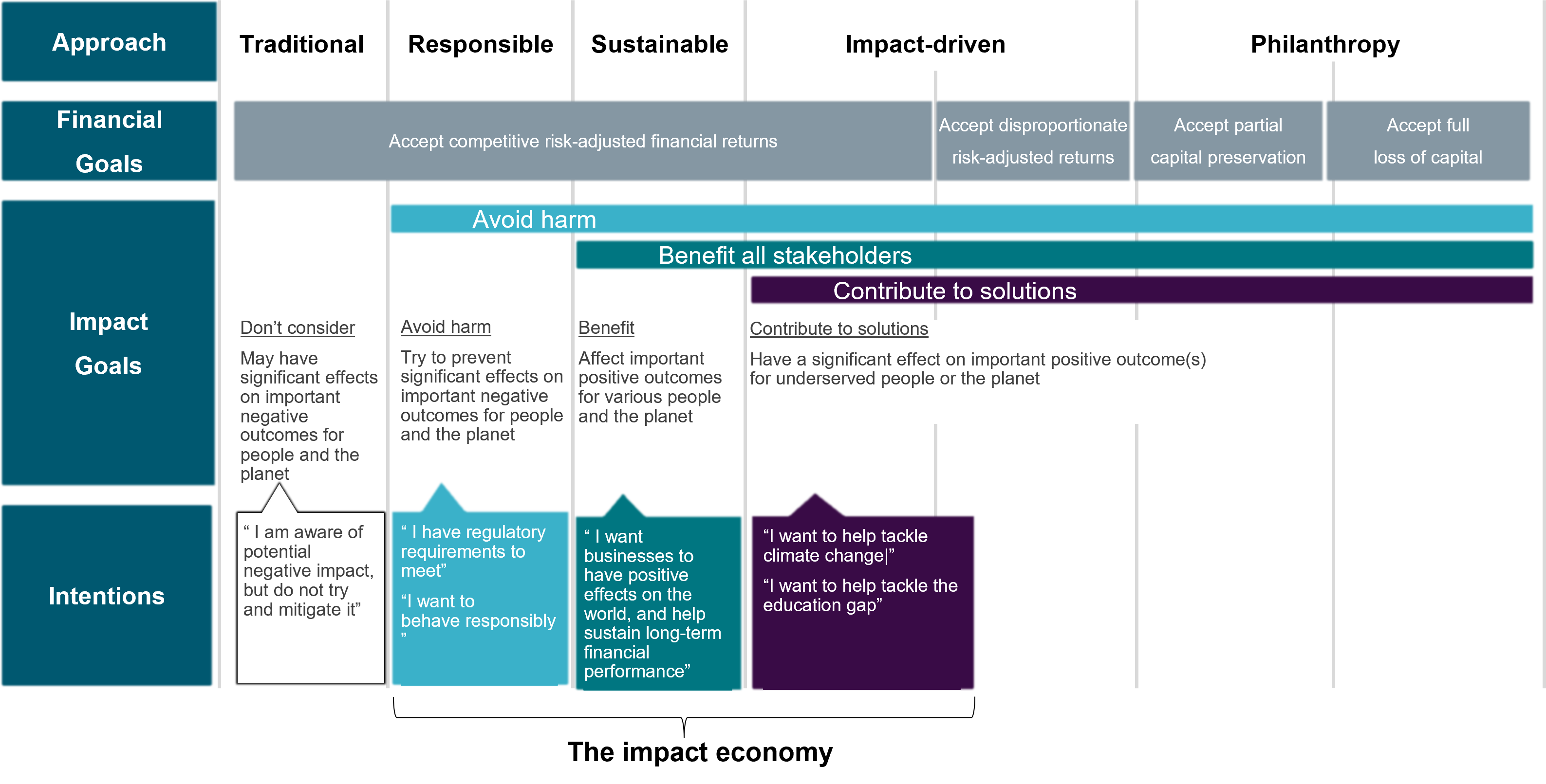

At present, ‘impact investing’ remains a somewhat niche consideration for investors, often approached via a siloed allocation and/or a specific mandate(s). That being said, we see proponents increasingly encouraging investors to consider ‘impact’ across their full investment portfolio. After all, every single investment has a variety of environmental and social effects—both negative and positive. This is the increasingly widely recognised concept of ‘double materiality’: the notion that companies are affected by ESG issues (‘outside-in’) but, at the same time, are having an effect on society and the environment (‘inside-out'), such as contributing to biodiversity loss.

One related term that investors will increasingly see referenced is the ‘Impact Economy’ : this involves paying regard to the positive and negative externalities (full costs and benefits) of all companies or productive activities and accounting for them more effectively. While impact investors are often under pressure to answer the question ‘does investing for impact entail sacrificing returns?’, concepts of this type push the debate towards a different question: ‘returns at what cost?’

The ’Impact Economy’ mindset extends the concept of impact investing—typically pushed to the far end of numerous industry infographics that show investment activities on a spectrum from ‘traditional’ to ‘philanthropic’—back into the mainstream. In this paradigm, impact investing would not be siloed but would be relevant to all asset managers and asset owners. As such concepts gain traction, investors should question fund managers of all types on their ability to assess a variety of types of impact and the ways in which they mitigate harmful outcomes as effective stewards of capital.

Source: bfinance, adapted from The Bridges Spectrum of Capital

Conclusion

Assessing investment managers’ ESG credibility, in an environment where ESG marketing is so dominant, is not an easy task. Investors that seek to deliver sustainable long-term returns, support decarbonisation or fulfil their mission to act as responsible stewards of capital must now wade through a minefield of style over substance, even though the substance itself has improved significantly over the past decade.

Yet there is, in fact, very clear differentiation between asset managers that are stronger and weaker on this subject. This is particularly visible when we look beyond some of the more popular headline variables (boxes that are increasingly ticked ‘yes’) and examine approaches in more detail. Effective due diligence that is sensitive to the specific asset class and spans both investment and operational aspects can identify best practice as well as highlighting ‘red flags’.

Moreover, an investor should keep a close eye on the selected asset managers’ capabilities following their appointment. The bar is being raised and ‘best practice’ is a continually moving target. We anticipate that institutional investors’ expectations and requirements will continue to escalate, with stakeholders becoming increasingly cognisant of the full overall cost—financial, environmental and social—of investment returns.

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

English (Global)

English (Global)  Français (France)

Français (France)  Italiano (Italia)

Italiano (Italia)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  English (Canada)

English (Canada)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)