bfinance insight from:

Chris Stevens

Senior Director, Diversifying Strategies

‘Energy transition’ tailwinds should, it is often argued, boost the prices of particular commodities in the years ahead. We can now even identify an emergent family of strategies dedicated to ‘energy transition commodities,’ providing investors with exposure to the likes of copper, aluminium, silver and platinum – with a slice of carbon allowances often thrown in for good measure. Yet investors considering direct commodity exposure must carefully weigh their tolerance for volatility and their patience for long-term performance, with the so-called green supercycle being hampered by weak global economic growth and political agendas.

Old asset class, new appeal?

Among the institutional investment community, enthusiasm for commodity investing has remained subdued since the 2008 financial crisis. The not-yet-published 2024 bfinance Global Asset Owner Survey will confirm that fewer than a quarter of ‘Asset Owners’ (pension funds, insurers, endowments and others) have direct exposure to commodities; this proportion has remained virtually unchanged since the last Global Asset Owner Survey was released in 2022. It is not hard to see why many investors have been hesitant to return to the asset class: even with very strong performance for the Bloomberg Commodities (BCOM) Index in 2021 (+27%) and 2022 (+16%), the annualised return over 2008-2022 was a dismal -2.6% with 17% volatility (not factoring in any fees or trading costs). The pre-2008 commodity boom – in which firms like Clive Capital, Bluegold, and Armajaro flourished – feels like a distant memory.

Yet the only constant is change. There is now a stronger case to be made for strategic allocations to commodities where investors seek to improve resilience to inflation and adapt to changing correlation dynamics. The 2022 surge drew attention from portfolio strategists, coming as it did in a year when both equities and bonds delivered material losses to investors’ portfolios.

There is, perhaps, an even more clearly defined thematic case for the commodities most closely associated with the energy transition. The argument can be stated simply: enormous demand is going to clash with constrained supply. The global shift away from fossil fuel-based energy systems to more sustainable energy sources—and the associated need for electrification, energy storage and grid modernisation—will require enormous volumes of commodity resources. However, supply will be constrained by years of underinvestment, environmental restrictions on extractive activities and geopolitical disruptions.

There is little room for complacency in allocations: as illustrated by the collapse in lithium prices in 2023 (-80%, despite its importance in electric vehicles), near-term supply-demand dysfunctions can overwhelm well-founded long-term trends.

Commodity strategies with an ‘energy transition’ theme

Increasingly, we see commodity investment strategies focusing heavily on—or even explicitly branding themselves under—the theme of energy transition.

Investors can find a broad array of strategies focused on the commodity sector, spanning alternative investment managers (‘commodity hedge funds’), commodity-related equity strategies, diversified commodity strategies (where transition is considered as part of a broader process) and, finally, a small but growing number of dedicated commodity strategies where energy transition is the preeminent theme.

This last group is very nascent, in that strategies are either new (<2 years of track record) or have not yet launched, but the products are based on long-standing commodity investment capabilities and teams. No doubt there is a marketing angle to this development, with firms leaning into a popular thematic narrative to boost commodity strategies’ investor appeal. Yet the shift is also founded in investment beliefs: active managers are broadly over-weighting the relevant commodities irrespective of strategy label.

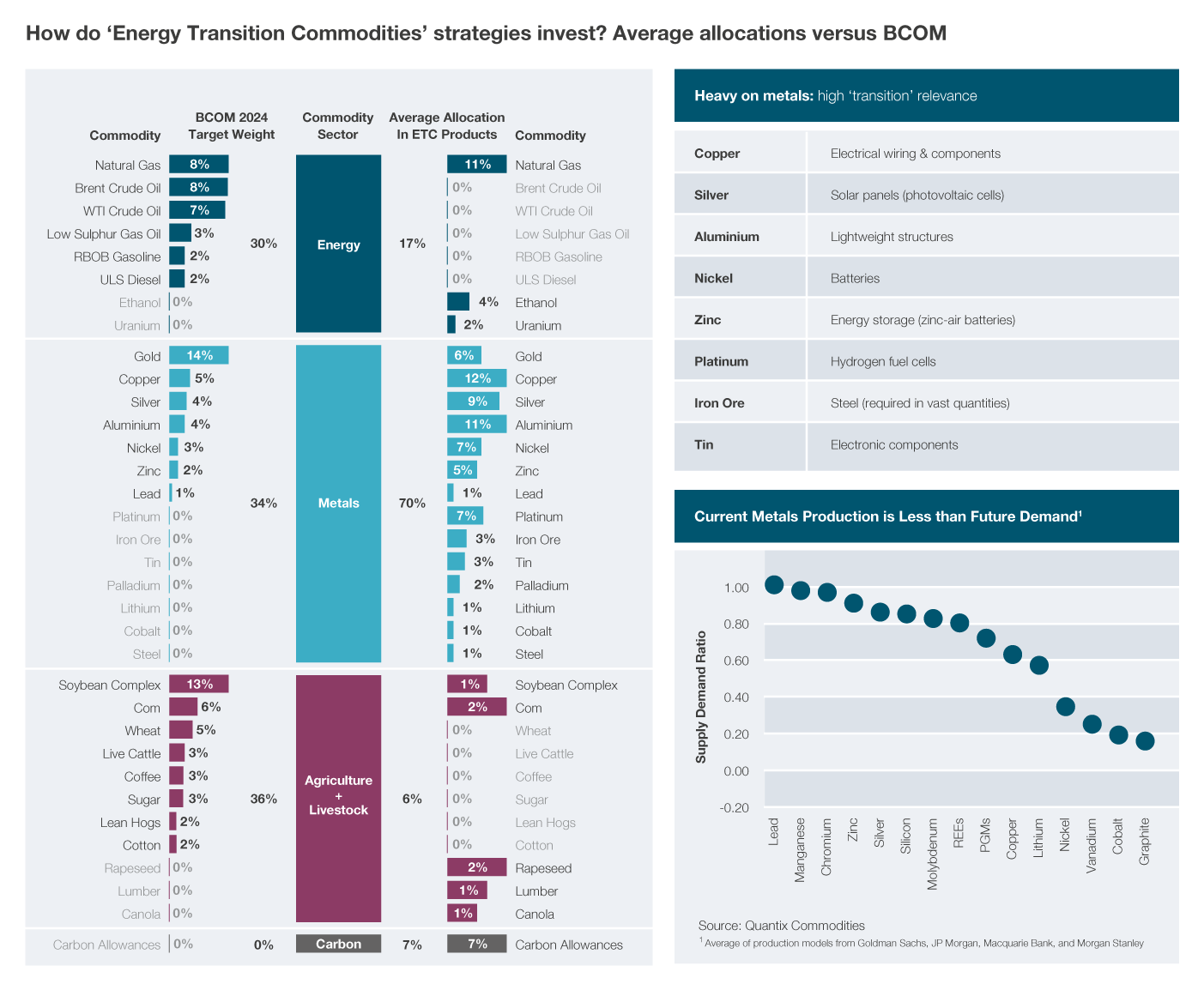

In a recent piece of analysis, bfinance examined a selection of commodity strategies where energy transition was emphasised as the central (or sole) theme. The figure below paints a snapshot of their views – comparing the average exposures of these strategies vs. the BCOM index.

Commodity investment strategies with an explicit ‘energy transition’ angle exhibit four common traits. These are, perhaps, already evident from the chart above: less exposure to energy, high exposure to industrial metals, minimal exposure to agriculture/livestock and the inclusion of carbon allowances.

- Light on energy. Where the BCOM has 30% in oil and gas (and the S&P GSCI has 58% in this sector), oil is uniformly absent from ‘energy transition commodities’ portfolios and the overall exposure to energy is lower at around 17%. Strategies took very different approaches to the subject of natural gas exposure: some saw this as out of scope for the theme, but a modest majority have natural gas exposure due to its status as the ‘cleanest’ fossil fuel that will help to bridge the gap as the world moves away from dirtier fuels and towards clean energy production. Ethanol and Uranium exposures featured in a minority of strategies as clean energy sources, but lower market liquidity is restrictive on materially upsizing these exposures. Whilst out of the scope of this piece, the imbalances between index weights and the desire to gain exposure to energy transition-related commodities means investors should give thought to the appropriateness of passive, benchmark-orientated strategies.

- Heavy on metals. As illustrated above, overweight positions to industrial metals are perhaps the defining feature of transition-oriented commodity investment strategies, due to their importance in energy production, energy storage, electrification and more. Commodity managers anticipate significant market tailwinds, driven by the growing demand from energy transition commitments and underinvestment in production to date (detailed further below).

- Minimal agriculture and livestock. Most of the agricultural sector is largely seen as irrelevant to the transition theme (e.g. coffee, sugar), while the livestock markets can be viewed as problematic, being carbon intensive protein sources. A minority of managers saw a role for certain agricultural exposures, particularly corn and the soybean complex (beans, meal, oil) that are used in biofuel production.

- Carbon allowances. A majority of dedicated energy transition commodity strategies analysed above included allocations to the regulated carbon markets. It is a distinctive feature: these markets do not feature in traditional commodity strategies or benchmarks. European allowances are widely used, as may be expected due to the liquidity and maturity of that market, but US and UK exposures were also present.

Copper in focus

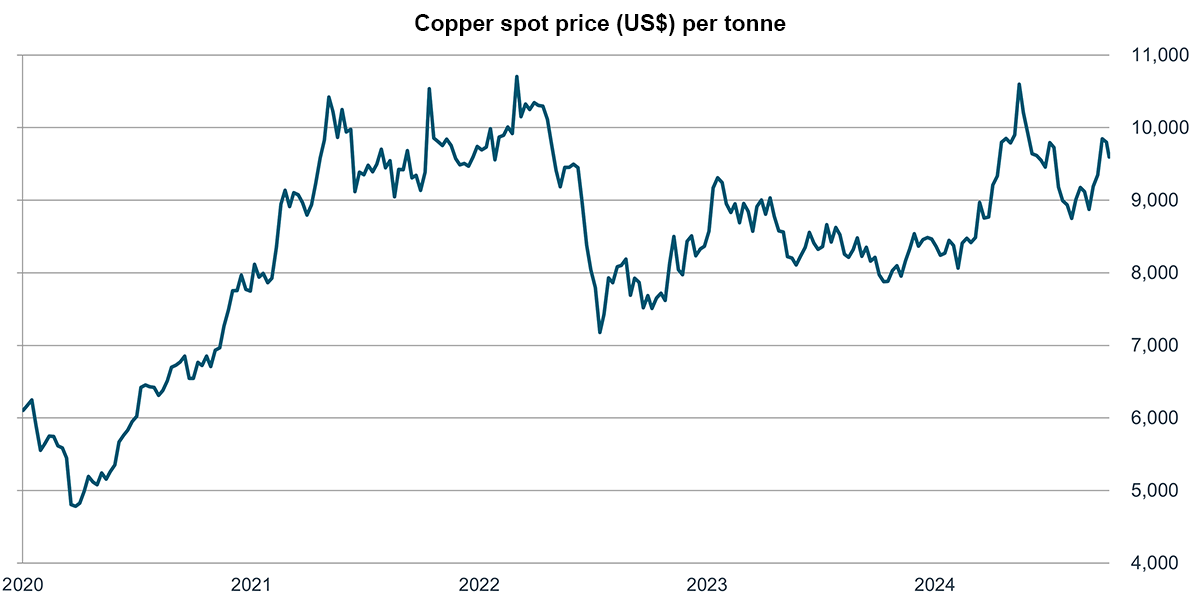

On average, as shown above, ‘energy transition commodities’ strategies have copper as their single largest exposure (12%). Copper presents an intriguing case study, illustrating how the tailwinds of structural demand can meet headwinds in the form of temporary supply-demand imbalances (e.g. weak demand from electric vehicle producers in 2023) and anaemic global economic growth.

The International Monetary Fund recently calculated that existing levels of copper production will meet just 60% of anticipated demand between 2021 and 2050. This includes notable expected demand from electric vehicle producers: one electric car typically contains more than 80kg worth of copper. Other green technologies—such as solar and wind power—demand significant amounts of copper in generation, transmission and storage installations. The supply of copper, however, has been flat in recent years and is widely predicted to fall in the near term. Australia has seen copper mine closures as production has become less economically attractive, and there have been multiple issues in the South American mines that dominate production.

Yet one would struggle to identify these potentially favourable supply-demand dynamics from the copper price alone, as shown in the chart below. Near-term pessimism about global growth, and particularly Chinese demand, has kept a cap on prices – which in turn raises the likelihood of continued underinvestment in production, further exacerbating expected future imbalances. The prevailing view from commodity managers: prices will have to rise.

Source: Bloomberg

Conclusion

While the commodities closely associated with the energy transition do hold significant long-term promise, investors must approach these markets with care. Short-term factors—such as fluctuations in global growth, geopolitical instability and more—can undermine long-term trends. Emerging markets (the source of many raw commodities) are particularly vulnerable to political risk. China is a key driver of demand, with markets responding to shifts in the country’s economy and policies. Complexities, such as substitution effects when prices for certain commodities become prohibitively high, further complicate the picture for investors.

Effective active management is essential for navigating the risks and seizing the opportunities that commodities may present through the ‘energy transition.’ By adjusting allocations in response to evolving supply/demand dynamics, asset managers can benefit from the ‘green supercycle’ dynamics while mitigating considerable downside risks.

Important Notices

This commentary is for institutional investors classified as Professional Clients as per FCA handbook rules COBS 3.5R. It does not constitute investment research, a financial promotion or a recommendation of any instrument, strategy or provider. The accuracy of information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified. Opinions not guarantees: the findings and opinions expressed herein are the intellectual property of bfinance and are subject to change; they are not intended to convey any guarantees as to the future performance of the investment products, asset classes, or capital markets discussed. The value of investments can go down as well as up.

Français (France)

Français (France)  Deutsch (DACH)

Deutsch (DACH)  Italiano (Italia)

Italiano (Italia)  Dutch (Nederlands)

Dutch (Nederlands)  English (United States)

English (United States)  English (Canada)

English (Canada)  French (Canada)

French (Canada)